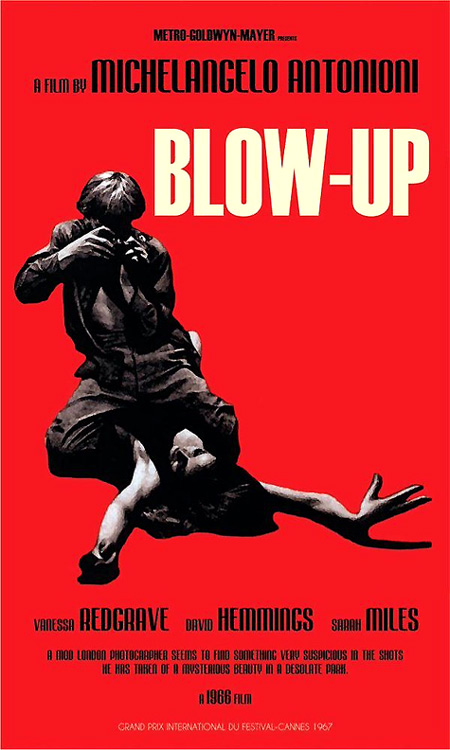

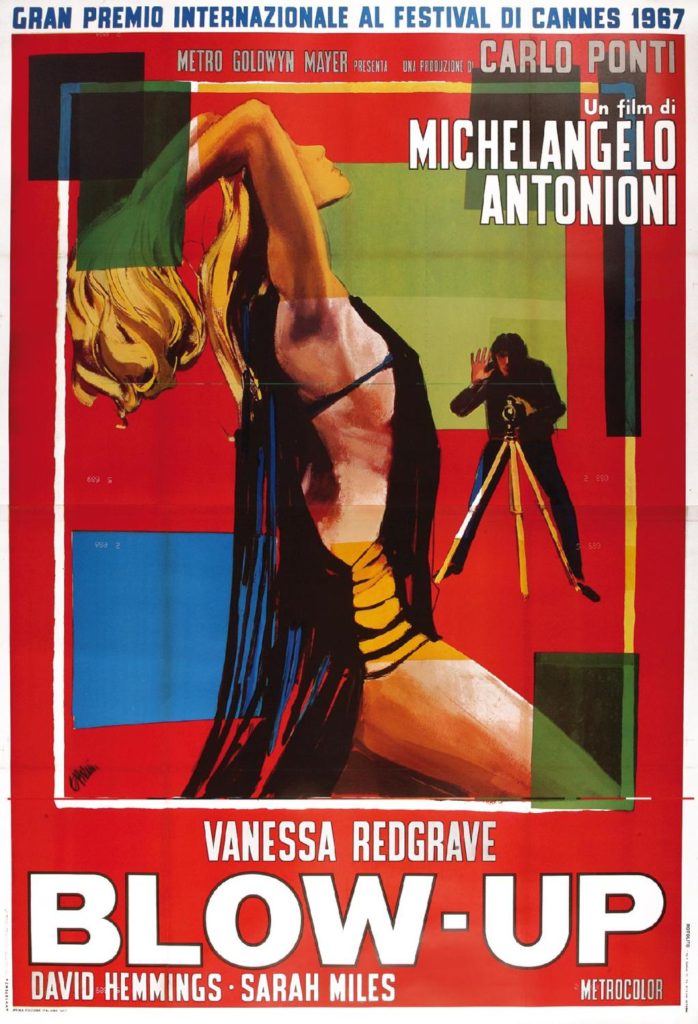

by Julio Cortazar

commonly known as “Blow Up” after Antonioni’s film which it inspired.

No one may ever know how to tell this story. Should it be in the first person or the second, using the third person plural or continually inventing forms that serve no purpose at all? If we could say: I they saw the moon rise, or: the inner core of my our eyes hurts, and, most of all: you the blonde woman were the clouds that keep racing ahead of my your her our all of your faces. What the hell.

While we’re on the subject, if I could go drink a Bock around the corner and have the typewriter continue on its own (because I write on a typewriter), that would be perfection. And that is not just a figure of speech. Perfection, yes, because here the shortcoming of having to tell a story likewise involves a machine (of another kind, a Contax 1.1.2), and the best thing would be for one machine to know more about another machine than I do, than you do, than she – the blonde – does, than the clouds. But it’s all only dumb luck. I know that if I left, this Remington would remain petrified atop the table with that air of double quietness that movable objects emit when they do not move. So I must write. One of us has to write, if all of this is to be told. Better that I be dead, better that I be less committed than the rest; I who do not see anything more than the clouds and who can think without distractions (another passes by now, with a grey fringe), who can write without distractions, who can remember without distractions, I who am dead (and alive, this is not a matter of trickery – it’ll be evident once the moment arrives – because somehow I have to get started and so have begun from this point, that of back then, that of the beginning, which, after all, is the best of points whenever you want to tell a story).

Suddenly I ask myself why I have to say this, but if we began to wonder why we did everything we did, if we merely asked ourselves why we accepted an invitation to dinner (now a pigeon is passing, looks to me like a sparrow), or why when someone has just told us a good story, something like a tickle arises in our stomach and it won’t be still until we walk into the next office and, in turn, tell the story; thus as soon as this is done, we are well, we are happy and we can get back to work. As far as I know no one has ever explained this, so that the best thing to do is to drop our inhibitions and tell the story, because at the end of the day no one is ashamed of breathing or putting on his shoes. Those are things that are done, and when something odd occurs, when we find a spider inside one of the shoes or when we breathe we feel like broken glass, then there is something to tell, something to tell the boys at the office or the doctor. Oh, doctor, every time I breathe … Always tell the story, always get rid of that annoying tickle in the stomach.

And since we’re going to tell the story, let’s put things in some order. Let’s go down the stairs of this house, Sunday, the seventh of November, just a month ago. We go down five floors and it’s Sunday, with an undreamed-of sun for a November in Paris, with a great desire to walk around, to see things, to take pictures (because we are photographers, I am a photographer). I know that the most difficult thing will be finding a way to tell the story, and I am not afraid of repeating myself. It will be difficult because no one quite knows who he telling the story truly is, if I am he or this is what has occurred, or what I am seeing (clouds, and now and again a pigeon), or if I am simply recounting a truth which is only my truth, and therefore it is not the truth apart from the truth for my stomach, for my desire to run out the door and, in some way, to put an end to all this, regardless of what may happen.

We are going to tell the story slowly, and we are going to see what happens as I write. If I am replaced, if I no longer know what to say, if the clouds end and something else begins (because it cannot be that one simply sees clouds passing continuously, and now and again a pigeon), if something from all of this … And after the “if,” what will I put down, how will I correctly finish my sentence? But if I start to ask questions I will not tell any story at all; better to tell, perhaps the process of telling the story will be like a response, at least for someone who might read it.

Roberto Michel, Franco-Chilean, translator and amateur photographer in his free time, stepped out of number 11 on the Rue Monsieur LePrince on Sunday, November 7th of the current year (now two smaller ones pass by with silver borders). He had spent the last three weeks working on the French version of a contract on the recusations and recourses of José Norberto Allende, professor at the University of Santiago. Wind in Paris is an oddity, much less wind that swirled around the corners and rose in punishment against the old wooden shutters, after which surprised old ladies commented in various ways on the instability of the weather these last few years. But the sun was out as well, riding the wind and friend to the cats, for which nothing would have stopped me from turning around towards the wharfs of the Seine and taking some pictures of the Ministry and Sainte-Chapelle. It was hardly ten o’clock and I calculated that the light would be good until about eleven, the best possible in autumn. To kill some time I moved on to Isle Saint-Louis then walked towards the Quai d’Anjou, gazed for a while at the Hotel Lauzun, recited some fragments from Apollinaire that always come to mind whenever I pass the Hotel Lauzun (and this ought to have reminded me of yet another poet, but Michel is a stubborn ox). And so, when all of a sudden the wind ceased and the sun became at least twice as large (I mean twice as warm, but in reality this is the same), I sat upon the parapet and felt, on this Sunday morning, terribly content.

Among the many ways of combating oblivion and nothingness, one of the best is taking photos, an activity which should be taught to children at an early age. It requires discipline, training in aesthetics, a good eye and sure hands. You aren’t simply lurking in wait of the lie like some reporter or catching the moronic silhouette of the big shot coming out of 10 Downing Street. In any case, when one is abroad with a camera one is almost obliged to be attentive, so as not to lose that rough and delicious career of sunlight on an old stone, or the dancing braids of a girl returning with a loaf or a bottle of milk. Michel knew that the photographer always operated like a permutation of his own personal manner of seeing the world, all the more since his camera rendered him insidious (now a large, almost black cloud passes by). But he did not mistrust this fact, knowing full well that he could leave the house without the Contax and still recuperate the distracted tone, the vision bereft of framing, the light without diaphragm or 1/250 shutter speed. Just now (what a word, now, what a stupid lie) I could have remained seated on the parapet above the river, watching the red and black pine needles pass, without it occurring to me to think of the scenes photographically, letting myself go to things letting themselves go, and running to stand still with time. And the wind was not blowing.

Afterwards I went on towards the Quai de Bourbon until I reached that point on the isle where an intimate chat (intimate because it was short and not because it was demure, as here one suckles both the river and the sky) can be enjoyed and then re-enjoyed. There was no one there apart from a couple and, of course, some pigeons, perhaps one of those passing now as far as I can see. With one movement I installed myself on the parapet and let myself be enveloped and attacked by the sun, on my face, my ears, my two hands (I kept my gloves in my pocket). I didn’t feel like taking any photos, and I lit a cigarette to have something to do; I believe it was in that moment, as the phosphorus of the tobacco drew closer, that I saw the boy for the first time.

What I had taken to be a couple seemed much more like a boy with his mother, although at the same time I noticed that it was not a boy with his mother, and that it was a couple in the sense that we always bestow upon couples when we see them leaning in parapets or kissing on public square benches. As I had nothing to do, I had enough time to ask myself why this boy was so nervous, why he so resembled a foal or a hare, placing his hands in his pockets, immediately taking one out and then the other, passing his fingers over his skin, changing his posture, and, most of all, because he was clearly afraid – this one could deduce from his every gesture – a suffocated fear of embarrassment, an impulse to throw himself back that came off as if his body were on the edge of flight, containing himself in a final and painful dignity.

So clear was all this from here, five meters away – and we were alone against the parapet, at the end of the isle – that initially the boy’s fear did not allow me to get a good look at the blonde woman. Now, when I think about it, I see her much better in this first moment when I was able to read her face (she had suddenly turned around like a copper weathercock, and her eyes, her eyes were there) when I vaguely understood what could be occurring at this moment to the boy and I said to myself that it was worth staying and watching (the wind lifted those words, scarcely murmured). If there’s something I know how to do, I think I know how to watch; and I also know that everything oozes falsity because it is what most casts us out of ourselves, without the slightest guarantee, as a smell, or (but Michel is quick to digress, one shouldn’t let him recite at ease). In any case, if the probable falsity has been predicted beforehand, looking again becomes possible; perhaps it suffices to choose well between looking and the look, stripping things of so much foreign clothing. And, of course, all of this is quite difficult.

I remember the boy’s face more than his actual body (this will be understood later), while now I am certain that I remember the woman’s body much better than her face. She was thin and svelte – two unfair words to say what she was – and dressed in a leather coat that was almost black, almost long, almost beautiful. All the wind of that morning (now it was hardly blowing at all, and it wasn’t cold) had passed over her blonde hair that cut out a shape from her cheerless, white face – two unfair words – and left the world standing and horribly alone before her black eyes, her eyes which fell upon things like two eagles, two leaps into the void, two gusts of green mud. I am not describing anything; rather, I am trying to understand. And I said two gusts of green mud.

Let’s be fair, however: the boy was rather well-dressed and sported yellow gloves that I could have sworn belonged to his older brother, a law or sociology student. It was funny to see the fingers of the gloves peering out from his jacket pocket. For a long while I did not see his face, hardly a profile, that wasn’t half-bad – an astonished bird, the angel of Fra Filippo, rice and milk – and the back of an adolescent who wanted to go in for judo and who had already fought a couple of times for an idea or a sister. At two o’clock sharp, perhaps at three o’clock sharp, one found him dressed and fed by his parents, but without a cent to his name, having to deliberate with his comrades before choosing a coffee, a cognac, or a pack of cigarettes. He would walk the streets thinking about his female classmates, about how good it would be to go to the movies and see the latest film, or buy novels or ties or bottles of liquor with green and white labels. In his house (his house would be respectable; lunch would be at twelve and there would be romantic landscapes on the walls with a dark foyer and a mahogany umbrella stand by the door) his homework time would slowly inundate him, as would being mama’s great hope, resembling papa, and writing to his aunt in Avignon. For that reason, every street, all the river (but without a cent) and the mysterious city of fifteen years with its signs on its doors, its spine-tingling cats, the carton of French fries for thirty francs, the porno magazine folded in four, solitude as a hole in his pockets, those happy meetings, the fervor for so many incomprehensible things – things, however, illuminated by a complete love – for the availability akin to the wind and the streets.

This biography was the boy’s as well as any boy’s, but him I now saw isolated, turned solely towards the presence of the blonde woman who kept on talking to him. (I am tired of insisting, but two long, frayed clouds have just passed. I think this morning I did not look once at the sky, since as soon as I presented what happened with the boy and the woman I could do nothing but watch them and wait, watch them and …). In summary, the boy was uneasy and, without much effort, one could guess what had just happened a few minutes ago, at the most half an hour ago. The boy had arrived to the end of the isle, seen the woman and found her attractive. The woman had been expecting this because she was here waiting for it, or perhaps the boy arrived before the woman and she saw him from a balcony or a car, and went out to meet him, starting up conversation on any old subject. And surely from the very beginning he was scared of her and wished to escape, and, of course, he would stay, cocky and sullen, feigning experience and a pleasure in risk and adventure. The rest was easy because it was taking place five meters from me and anyone could have measured the stages of the game, the ridiculous parrying; his greatest charm was not his present, but his prediction of the dénouement. The boy would have given the pretext of an appointment, some kind of obligation, and would have run off stumbling and confused, wishing to walk with self-assurance, naked beneath the mocking gaze which would follow him until the end. Or perhaps he would remain, fascinated or simply incapable of taking the initiative, and the woman would begin to caress his face, play with his hair, speak to him voicelessly, and then quickly grab him by the arm to take him with her, as he, with an unease that perhaps began to acquire desire, the risk of adventure, roused himself to put his arm around her waist and kiss her. All this could have occurred, but may not have occurred, and Michel perversely waited, sitting in the parapet and, without even realizing it, readying the camera to take a picturesque photo in a corner of the isle with a couple gazing at one another and having nothing in common to talk about.

Curious that this scene (the nothing scene, almost: the two who are there, unequally young) had an aura of disquiet. I thought this was something that I inserted; I also thought that my picture, if I were to retrieve it, would restore matters to their silly truth. I would have liked to know the thoughts of the man in the gray hat seated at the wheel of the car stopped at the loading dock which was on the sidewalk, and whether he was reading the paper or sleeping. I had just discovered why people within a car almost disappear, lost in that wretched private suitcase of beauty which lends them movement and danger. Nevertheless, the car had been there all this time, forming part (or deforming this part) of the isle. A car: how should one say an illuminated street lamp, a public square bench. Never the wind, the light of the sun, these materials were always new for the skin and the eyes, and also the boy and the woman, alone, placed here so as to alter the isle, so as to show it to me in another way. In the end, it might have occurred that the man with the newspaper had been attentive to what was happening and felt, like I, the malignant aftertaste of all expectations.

Now the woman had suavely turned around until the boy was between her and the parapet; I could see him almost in profile and he was taller, but not much taller, and nevertheless the woman seemed to be dangling above him (her laugh, all of a sudden, a whip of feathers), crushing him by simply being there, smiling, passing her hand through the air. Why wait any longer? With a sixteen diaphragm, with framing in which the horrible black car would not be included but the tree would, I would need to snap a space especially grey …

I raised the camera, pretended to study an angle that did not include them, and remained lurking in wait, certain that, at last, I would catch the revelatory gesture, the expression that summed it all up, the life which movement encompassed but which a rigid face destroyed by sectioning off time, if we did not choose that essential, imperceptible fraction. I did not have to wait long.

The woman advanced in her task of gently binding the boy, of plucking, one by one, the remaining fibers of his freedom, in the slowest and most delicious of tortures. I imagined the possible consequences (now a small, foamy cloud appears, almost alone in the sky), foresaw the arrival at the house (a first-floor entryway most likely, which she would stuff with cushions and cats), and sensed the boy’s embarrassment and his desperate decision to conceal it, to keep on pretending that nothing was new to him. Closing my eyes, if it is I who closed them, I put the stage in order: the mocking kisses, the woman tenderly rejecting those hands that sought to undress her, like hands in novels did, on a bed with a purple comforter, and obliging him instead to stop trying to remove her clothes, truly then mother and son beneath the opalines’ yellow light. And everything would end as it always did, perhaps, but perhaps everything was different, and the initiation of the adolescent did not take place, perhaps they did not allow it to happen, from a long preface where clumsy embraces and exasperating caresses, the shuttle of hands, resolved itself into who knows what, into a separate but solitary pleasure, into the petulant mixed denial with the art of fatiguing and disconcerting so much injured innocence. It could have been like this, it could well have been like this; that woman was not looking for a lover in the boy, at once instructing him for an impossible aim of understanding – if he didn’t think of it as a cruel game – the desire of desiring without satisfaction, of arousing herself for someone else, for someone who in no way could be this boy.

Michel is guilty of literature, of unreal fabrications. There is nothing he likes better than to imagine exceptions, individuals outside of the species, monsters not always repugnant. But this woman invited invention, giving him perhaps the keys to hit upon the truth. Before he left, and now that my memories have been filled for many days since I am prone to rumination, I decided not to lose a moment more. I gathered everything in my viewfinder (the photos with the tree, the parapet, the eleven o’clock sun) and took the photo. All in enough time to understand that the two had noticed and that they were looking at me, the boy was surprised and almost interrogative, while she was irritated; and resolutely hostile were her body and her face that knew themselves to have been stolen, ignominiously taken prisoner by a small chemical image.

I could tell this story with much detail, but it’s not worth it. The woman said that no one had the right to take a photo without permission and demanded that I hand over the roll of film. All this in a clear, dry voice and good Parisian accent rising with every phrase in color and tone. For my part I didn’t care much about relinquishing the roll of film, but anyone who knows me knows that you have to ask me willingly for things. As a result, I limited myself to the formulation of an opinion: namely, that photography was not only unprohibited in public places, but in fact enjoyed great official and private support. And while telling her this in meticulous detail, I was able to enjoy how the boy was withdrawing and staying back – somehow without moving – when all of sudden (it seemed almost incredible), he turned around and took off running, believing himself to be a poor fool walking when, in reality, he was fleeing in haste, passing to the side of the car, and losing himself like “a thread of the Virgin” in the morning air.

But the threads of the Virgin are also what we call the drool of the devil, or, more commonly, a cobweb. And Michel had to endure very precise imprecations, hear himself be labeled a meddler and an imbecile, and he deliberately made a fierce effort to smile and decline, with simple movements of his head, every cheap shot. When I was beginning to get tired I heard a car door slam. The man in the gray hat was there watching us. Only then did I understand that I was playing a role in the production.

He started walking towards us, carrying in his hand the newspaper which he had been pretending to read. What I most remember is the sneer of his mouth that covered his face in wrinkles, vacillating somewhat in location and form because his mouth was quivering and his grimace slipped from one side of his lips to the other like something independent and alive, something alien to the will. But the rest of it was rigid, a flour-coated clown or bloodless man, his skin dull and dry, his sunken eyes and his black, visible nostrils, blacker than his eyebrows or his hair or his black necktie. His was a cautious walk, as if the pavement hurt his feet. I saw that he had on patent leather shoes, with a very thin sole that must have cursed the street’s every unevenness. I don’t know why I had gotten down from the parapet; I don’t know full well why I decided not to give them the photo, to refuse this demand in which I sensed fear and cowardice. The clown and the woman convened in silence: we formed a perfect, unbearable triangle, something destined to break with a snap. I laughed in their faces and set off on my way, I suppose a little more slowly than the boy. When I had come to the first houses, on the side of the iron footbridge, I turned back to look at them. They were not moving, but the man had dropped his newspaper; it seemed to me that the woman, with her shoulders against the parapet, was passing her hands over the stone in that classic and absurd gesture of the persecuted seeking a way out.

What happens next occurred here, almost just now in fact, in a fifth-floor room. Several days passed before Michel developed that Sunday’s pictures; his shots of the Ministry and Sainte-Chapelle were what they should have been. He found two or three test shots that he had already forgotten, a feeble attempt to capture a cat perched on the roof of a urinal alley, as well as the photo of the blonde woman and the adolescent. The negative was so good that he prepared an enlargement; the enlargement was so good that he made another, much larger one, almost the size of a poster. It did not occur to him (now he wonders and wonders) that only the photos of the Ministry merited so much work. From the entire series, the snapshot on the edge of the isle was the only one that interested him. He pinned the enlargement on a wall of the room and that first day he spent a while gazing at it and remembering it in that comparative and melancholy operation of remembrance in the face of lost reality; his frozen memory, like every photo in which nothing was missing, not even and most of all nothing, the true scene setter.

The woman was there; the boy was there; the tree above their heads was rigid; the sky as fixed and unmoving as the stones of the parapet, the clouds and stones combined in a single inseparable material (now there comes one with sharp edges, running like the head of a storm). The first two days I accepted what I had done, from the photo in and of itself to the enlargement on the wall, and I didn’t even ask myself why I would interrupt at every opportunity the translation of the contract of José Norberto Allende to revisit the face of the woman and the dark stains of the parapet. The first surprise was stupid; it would never have occurred to me to think that when we look at a photo from the front, the eyes repeat exactly the position and the vision of the lens; it is these things which are taken for granted, which it doesn’t occur to anyone to consider. From my chair, with my typewriter before me, I looked at the photo over there, three meters away. And then it occurred to me that I had placed myself at exactly the point of observation of the lens. It was very good here; doubtless it was the most perfect way to appreciate a photo, although looking at it diagonally could have its charms as well as its discoveries. Every few minutes, for example when I could not find a way of saying in good French what José Alberto Allende was saying in good Spanish, I raised my eyes and looked at the photo; sometimes I was drawn to the woman, sometimes to the boy, sometimes to the pavement where a dry leaf had admirably settled so as to assess the nearby area. So I took a break from my work for a while, and included myself yet again in that morning in which the photo was steeped. I remembered ironically the woman’s furious face as she protested my picture-taking, the boy’s ridiculous and pathetic flight, the entrance onto the scene of the man with the white face. In my heart I was content with myself: my part had not been too outstanding, for if the French have been given the gift of witty retort, I did not understand why I had chosen to leave without a completed demonstration of privileges, prerogatives and civil rights. The important thing, the truly important thing, was to have abetted the boy in his timely escape (this in the event that my theories were correct, which has not been sufficiently tested, but the flight itself seemed to show that they were). By merely meddling I had given him an opportunity to benefit at last from his fear and to accomplish something useful. Now it would be regretted, diminished, and he would feel himself to be less of a man. But this was better than the company of a woman capable of looking like he was looked at on the isle; Michel is at times a puritan, believing that one should not be corrupted by force. In his heart, this photo had been a good deed.

But not because it was a good deed did I look at it between paragraphs of my work. At that time I did not know why I was looking at it, why I had pinned an enlargement to the wall. Perhaps this may be what happens with all fatidic actions, perhaps this may be the condition of their fulfillment. I believe that the almost furtive trembling of the leaves of the tree did not alarm me, that I followed a sentence already begun and I rounded it out nicely. Habits are like great herbaria: at the end of the day an eighty by sixty centimeter enlargement looks like a movie screen where on the end of an isle a woman is talking to a boy as a tree shakes its dry leaves above their heads.

But the hands were already too much. I had just written: Donc, la seconde clé réside dans la nature intrinsèque des difficultés que les sociétés (“Therefore the second key resides in the intrinsic nature of the difficulties which companies …”) – and I saw the woman’s hand which began to close slowly, finger by finger. Of me nothing remained, a sentence in French that might never have ended, a typewriter which tumbles to the floor, a chair which screeches and shakes, a patch of fog. The boy had lowered his head like a boxer who cannot continue and who awaits the coup de grace; he had lowered the collar of the overcoat, looking more than ever like a prisoner, the perfect victim who aids in the catastrophe. Now the woman was whispering in his ear, and her hand opened again so as to be placed upon his cheek, to caress it and caress it, burning it in no haste. The boy was less embarrassed than mistrustful; once or twice he gazed beyond the woman’s shoulder and she went on talking, explaining something that made her keep looking over to the area where, Michel knew full well, the car with the man in the gray hat was located, carefully omitted in the photo but reflected in the boy’s eyes and (how could one doubt this now) the woman’s words, in the woman’s hands, in the woman’s vicarious presence.

When I saw the man coming, stopping near them and watching them, his hands in his pockets with an air of something between rushed and demanding, an owner about to whistle for his dog after the latter’s frolicking about the square, I understood, if this was to be understood, what had to have been happening, what had to have happened, what would have had to happen at that moment, between these people, over there where I had arrived to disrupt a certain order, innocently interfering in that which had not happened but which now was about to happen, which now was about to be fulfilled. And, therefore, what I had imagined was far less horrible than the reality, this woman who was not here for herself, who was not caressing or proposing or breathing for her own pleasure, or to capture that disheveled angel and toy with his terror and his yearning grace. The true master was waiting, smiling petulantly, already sure of the performance. He was not the first to order a woman into the vanguard, to bring her prisoners bound with flowers. The rest would be so simple: the car, some house somewhere, the drinks, the arousing sheets, the tears all too late, the awakening in hell. And I could have done nothing, this time I could have done absolutely nothing. My power had been a photo, this one, there, in which they would take their vengeance on me and show me openly what was about to take place. The photo had been taken and the time had passed: we were so far from one another, the corruption assuredly completed, the tears shed, and the rest conjecture and sadness. Suddenly the order was inverted, they were alive, moving, deciding and being decided, heading towards their future. And I from this side, prisoner of another time, of a room on the fifth floor, of not knowing who this woman and this man and this boy were, of being nothing more than the lens of my camera, something rigid, incapable of intervention.

On me they were playing the most horrible trick of all, that of deciding in the face of my own powerlessness, that of having the boy look at the flour-faced clown one more time, and having me understand that he was going to accept, that the proposal contained money or deception, and that I could not shout out for him to flee, or simply again facilitate his exit with a new photo, a small and almost humble intervention that disrupted the scaffolding of drool and perfume. Everything was going to resolve itself there, in that instant; it was something like an immense silence that had nothing to do with physical silence. This silence lay down and armed itself. I think I screamed, I screamed a terrible scream, and at that very second I knew that I was beginning to get closer, ten centimeters, one step, another step, the tree was in the forefront turning its branches rhythmically, a stain from the parapet jumped from the picture, the woman’s face, turned towards me as if surprised, was growing. And so I turned a little bit – I mean to say that the camera turned a little bit – and without losing sight of the woman, it began to approach the man who was looking at me with those black holes he had in place of eyes, looking at me with either surprise or fury, with the desire of hammering me in the air. And at that instant I managed to see how a great bird out of focus swooped down once before my eyes, and I leaned against the wall of my room and was happy because the boy had just escaped, I saw him running, again in focus, fleeing with all his hair in the wind, learning at last to fly over the isle, reach the footbridge, and go back to the city. For the second time I was leaving them; for the second time I helped him escape and returned him to his precarious paradise. I remained panting before them; there was no need to go any further; the game had been played. Of the woman one could barely make out a shoulder and some of her hair, brutally cut by the picture of her face; but in the foreground was the man, his mouth agape. And there in his mouth I saw a black tongue flickering, and he was slowly raising his hands, bringing them also to the foreground, an instant still in perfect focus; he, after all, the lump who was erasing the isle, the tree, and I closed my eyes and wished to look no more. And I covered my face and broke out crying like an idiot. Now a large white cloud passes by, like all those days, all this countless time. What remains to be said is always a cloud, two clouds, or long hours of perfectly clear sky, rectangular purism hammered in with pins in the wall of my room. This was what I saw when I opened my eyes and dried them with my hands: a clear sky, and then a cloud coming in from the left, passing its grace slowly and then disappearing to the right. And then another, and instead at times everything becomes gray, everything is an enormous cloud, and suddenly the splashes of rain crackle, and for a long time it rains on this face, like crying in reverse, and little by little the picture becomes clear, perhaps the sun comes out, and once again the clouds appear, in twos and threes. And the pigeons, sometimes, and the odd sparrow.