Once upon a time, a school master from Granada was transferred to Almería. There, one of his daughters met a local boy. They married and had five children. One of them was my mother.

Just a simple family story at a time of great enthusiasm in a transforming country. They were talented engaged humanists. Their life, the life of their families and friends took a sudden tragic turn exactly 80 years ago.

As an introduction to this strange, dramatic story here are the fresh impressions of a tourist.

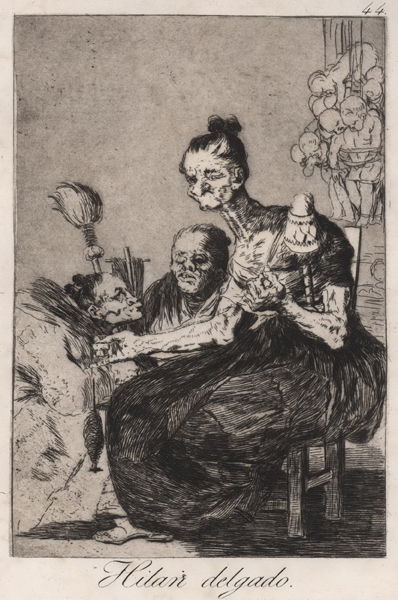

The year after Goya’s death, Washington Irving went from Seville to Granada. The trip took more than three days during witch he met Andalusia, the land, its people…

The Journey

By Washington Irving, from “Tales of the Alhambra”

In the spring of 1829, the author of this work, whom curiosity had brought into Spain, made a rambling expedition from Seville to Granada in company with a friend, a member of the Russian Embassy at Madrid. Accident had thrown us together from distant regions of the globe, and a similarity of taste led us to wander together among the romantic mountains of Andalusia. […]

And here, before setting forth, let me indulge in a few previous remarks on Spanish scenery and Spanish travelling. Many are apt to picture Spain to their imaginations as a soft southern region, decked out with the luxuriant charms of voluptuous Italy. On the contrary, though there are exceptions in some of the maritime provinces, yet, for the greater part, it is a stern, melancholy country, with rugged mountains, and long sweeping plains, destitute of trees, and indescribably silent and lonesome, partaking of the savage and solitary character of Africa. What adds to this silence and loneliness, is the absence of singing birds, a natural consequence of the want of groves and hedges. The vulture and the eagle are seen wheeling about the mountain-cliffs, and soaring over the plains, and groups of shy bustards stalk about the heaths; but the myriads of smaller birds, which animate the whole face of other countries, are met with in but few provinces in Spain, and in those chiefly among the orchards and gardens which surround the habitations of man. […]

But though a great part of Spain is deficient in the garniture of groves and forests, and the softer charms of ornamental cultivation, yet its scenery is noble in its severity, and in unison with the attributes of its people; and I think that I better understand the proud, hardy, frugal and abstemious Spaniard, his manly defiance of hardships, and contempt of effeminate indulgences, since I have seen the country he inhabits.

There is something too, in the sternly simple features of the Spanish landscape, that impresses on the soul a feeling of sublimity. […] Thus the country, the habits, the very looks of the people, have something of the Arabian character. The general insecurity of the country is evinced in the universal use of weapons. The herdsman in the field, the shepherd in the plain, has his musket and his knife. The wealthy villager rarely ventures to the market-town without his trabuco, and, perhaps, a servant on foot with a blunderbuss on his shoulder; and the most petty journey is undertaken with the preparation of a warlike enterprise. […]

The dangers of the road produce also a mode of travelling, resembling, on a diminutive scale, the caravans of the east. The arrieros, or carriers, congregate in convoys, and set off in large and well-armed trains on appointed days; while additional travellers swell their number, and contribute to their strength. In this primitive way is the commerce of the country carried on. […]

As these men have often their whole fortune at stake upon the burden of their mules, they have their weapons at hand, slung to their saddles, and ready to be snatched out for desperate defence; but their united numbers render them secure against petty bands of marauders, and the solitary bandolero, armed to the teeth, and mounted on his Andalusian steed, hovers about them, like a pirate about a merchant convoy, without daring to assault.

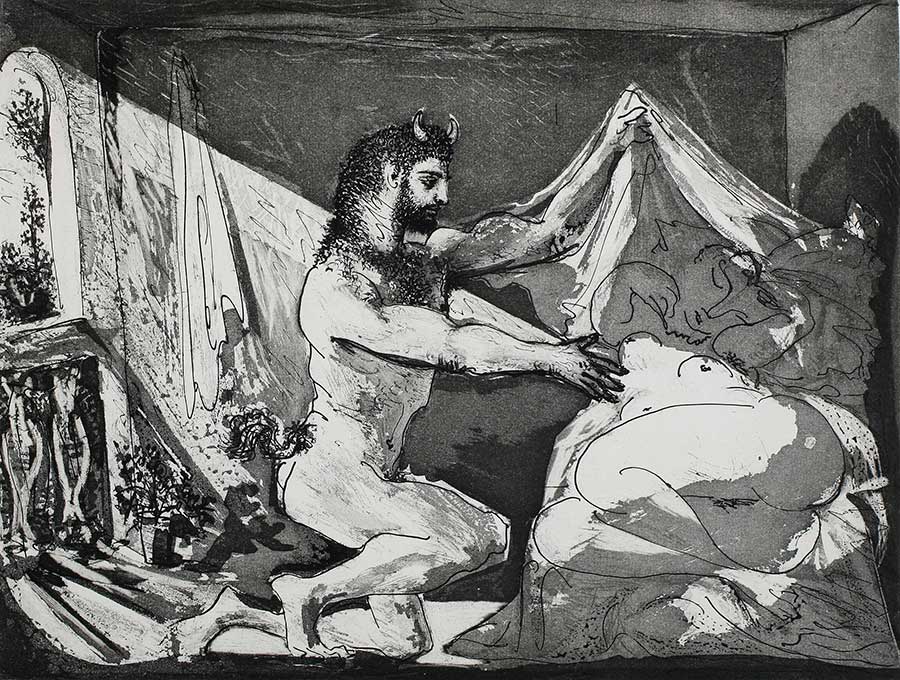

The Spanish muleteer has an inexhaustible stock of songs and ballads, with which to beguile his incessant wayfaring. The airs are rude and simple, consisting of but few inflections. These he chants forth with a loud voice, and long, drawling cadence, seated sideways on his mule, who seems to listen with infinite gravity, and to keep time, with his paces, to the tune. The couplets thus chanted, are often old traditional romances about the Moors, or some legend of a saint, or some love-ditty; or, what is still more frequent, some ballad about a bold contrabandista, or hardy bandolero, for the smuggler and the robber are poetical heroes among the common people of Spain. Often, the song of the muleteer is composed at the instant, and relates to some local scene, or some incident of the journey. This talent of singing and improvising is frequent in Spain, and is said to have been inherited from the Moors. There is something wildly pleasing in listening to these ditties among the rude and lonely scenes they illustrate; accompanied, as they are, by the occasional jingle of the mule-bell. […]

The ancient kingdom of Granada, into which we* were about to penetrate, is one of the most mountainous regions of Spain. Vast sierras, or chains of mountains, destitute of shrub or tree, and mottled with variegated marbles and granites, elevate their sunburnt summits against a deep-blue sky; yet in their rugged bosoms lie ingulfed verdant and fertile valleys, where the desert and the garden strive for mastery, and the very rock is, as it were, compelled to yield the fig, the orange, and the citron, and to blossom with the myrtle and the rose. […]

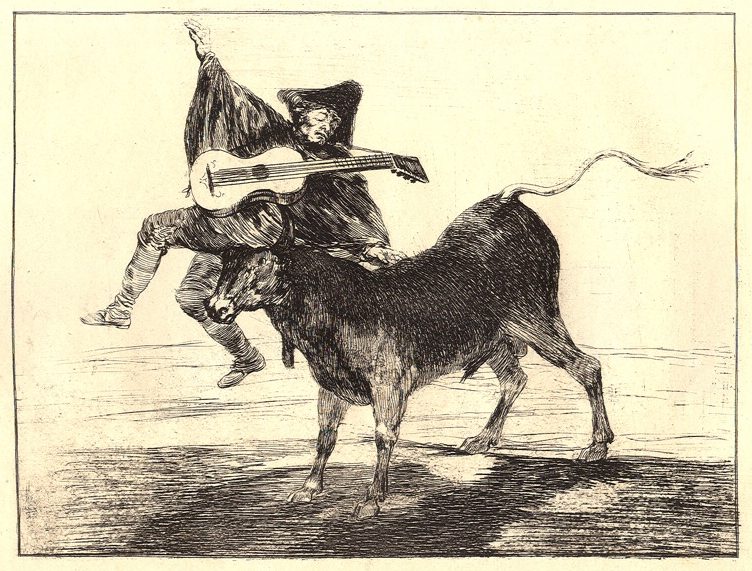

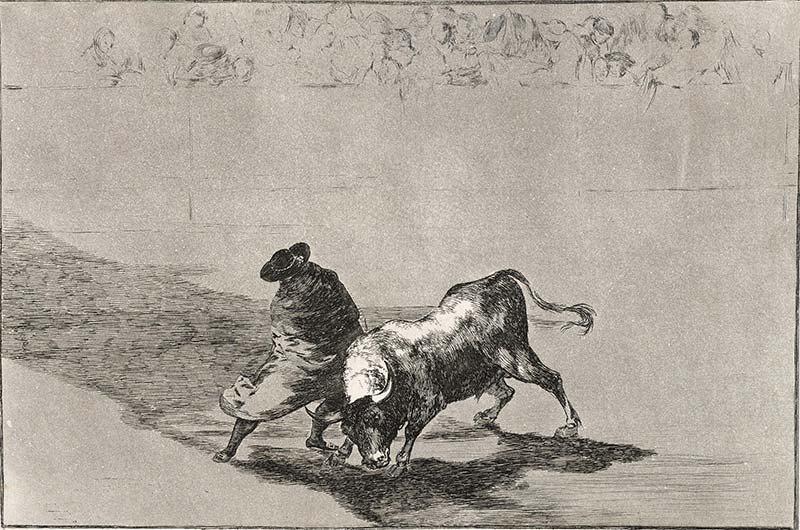

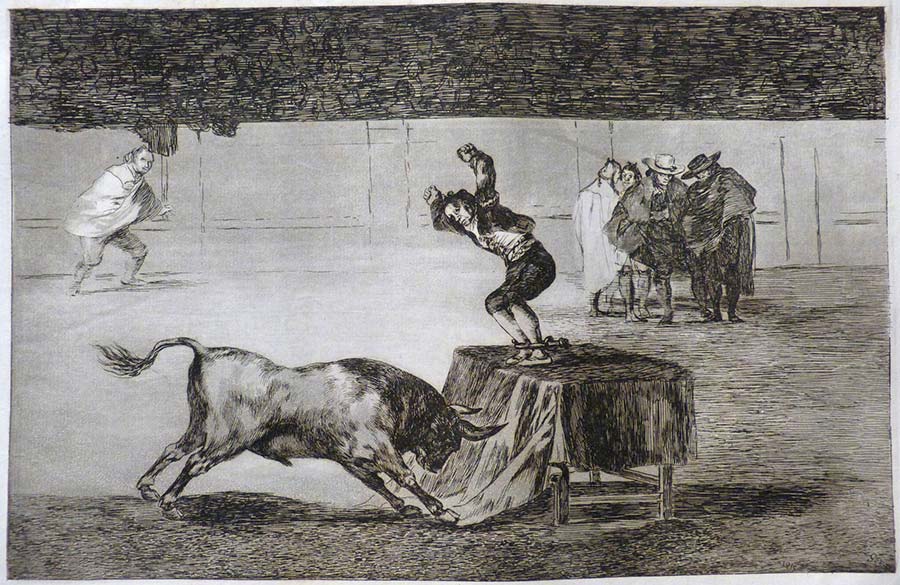

Sometimes the road winds along dizzy precipices, without parapet to guard him from the gulfs below, and then will plunge down steep, and dark, and dangerous declivities. Sometimes it struggles through rugged barrancos, or ravines, worn by winter torrents, the obscure path of the contrabandista; while, ever and anon, the ominous cross, the monument of robbery and murder, erected on a mound of stones at some lonely part of the road, admonishes the traveller that he is among the haunts of banditti, perhaps at that very moment under the eye of some lurking bandolero. Sometimes, in winding through the narrow valleys, he is startled by a hoarse bellowing, and beholds above him on some green fold of the mountain a herd of fierce Andalusian bulls, destined for the combat of the arena. I have felt, if I may so express it, an agreeable horror in thus contemplating, near at hand, these terrific animals, clothed with tremendous strength, and ranging their native pastures in untamed wildness, strangers almost to the face of man: they know no one but the solitary herdsman who attends upon them, and even he at times dares not venture to approach them. The low bellowing of these bulls, and their menacing aspect as they look down from their rocky height, give additional wildness to the savage scenery. […]

As our proposed route to Granada lay through mountainous regions, where the roads are little better than mule paths, and said to be frequently beset by robbers, we took due travelling precautions. Forwarding the most valuable part of our luggage a day or two in advance by the arrieros, we retained merely clothing and necessaries for the journey and money for the expenses of the road, with a little surplus of hard dollars by way of robber purse, to satisfy the gentlemen of the road should we be assailed.

Unlucky is the too wary traveller who, having grudged this precaution, falls into their clutches empty handed: they are apt to give him a sound ribroasting for cheating them out of their dues. “Caballeros like them cannot afford to scour the roads and risk the gallows for nothing.” […]

Such were our minor preparations for the journey, but above all we laid in an ample stock of good humor, and a genuine disposition to be pleased, determining to travel in true contrabandista style, taking things as we found them, rough or smooth, and mingling with all classes and conditions in a kind of vagabond companionship. It is the true way to travel in Spain. With such disposition and determination, what a country is it for a traveller, where the most miserable inn is as full of adventure as an enchanted castle, and every meal is in itself an achievement! Let others repine at the lack of turnpike roads and sumptuous hotels, and all the elaborate comforts of a country cultivated and civilized into tameness and commonplace; but give me the rude mountain scramble; the roving, haphazard, wayfaring; the half wild, yet frank and hospitable manners, which impart such a true game flavor to dear old romantic Spain!

Thus equipped and attended, we cantered out of “Fair Seville city” at half-past six in the morning of a bright May day, in company with a lady and gentleman of our acquaintance, who rode a few miles with us, in the Spanish mode of taking leave. […]

At Gandul we found a tolerable posada; the good folks could not tell us what time of day it was — the clock only struck once in the day, two hours after noon; until that time it was guesswork. We guessed it was full time to eat; so, alighting, we ordered a repast. While that was in preparation we visited the palace once the residence of the Marquis of Gandul. All was gone to decay; there were but two or three rooms habitable, and very poorly furnished. Yet here were the remains of grandeur: a terrace, where fair dames and gentle cavaliers may once have walked; a fish-pond and ruined garden, with grapevines and date-bearing palm-trees. Here we were joined by a fat curate, who gathered a bouquet of roses and presented it, very gallantly, to the lady who accompanied us.

Shortly after sunset we arrived at Arahal, a little town among the hills. We found it in a bustle with a party of miquelets, who were patrolling the country to ferret out robbers. The appearance of foreigners like ourselves was an unusual circumstance in an interior country town; and little Spanish towns of the kind are easily put in a state of gossip and wonderment by such an occurrence. Mine host, with two or three old wiseacre comrades in brown Cloaks, studied our passports in a corner of the posada, while an Alguazil took notes by the dim light of a lamp. The passports were in foreign languages and perplexed them, but our Squire Sancho assisted them in their studies, and magnified our importance with the grandiloquence of a Spaniard. […] The commander of the patrol took supper with us — a lively, talking, laughing Andaluz, who had made a campaign in South America, and recounted his exploits in love and war with much pomp of phrase, vehemence of gesticulation, and mysterious rolling of the eye. He told us that he had a list of all the robbers in the country, and meant to ferret out every mother’s son of them; he offered us at the same time some of his soldiers as an escort. “One is enough to protect you, senores; the robbers know me, and know my men; the sight of one is enough to spread terror through a whole sierra.” We thanked him for his offer, but assured him, in his own strain, that with the protection of our redoubtable squire, Sancho, we were not afraid of all the ladrones of Andalusia.

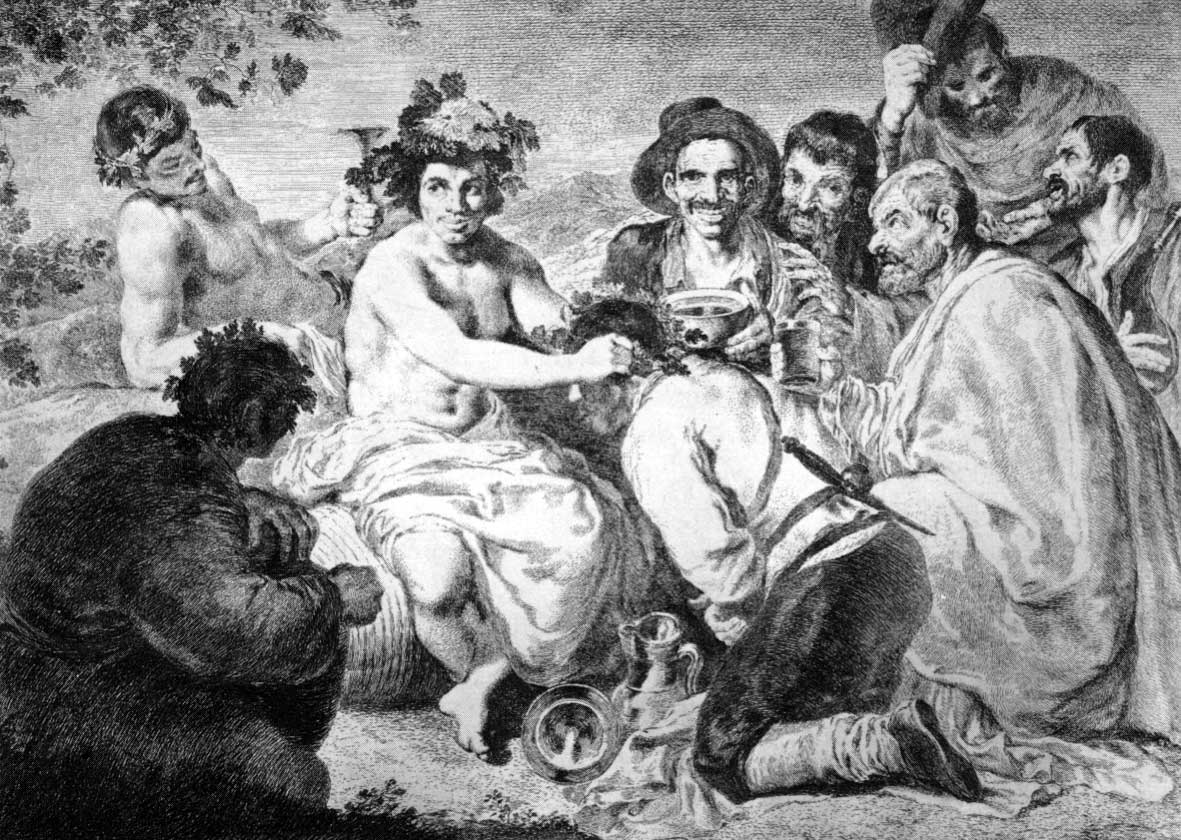

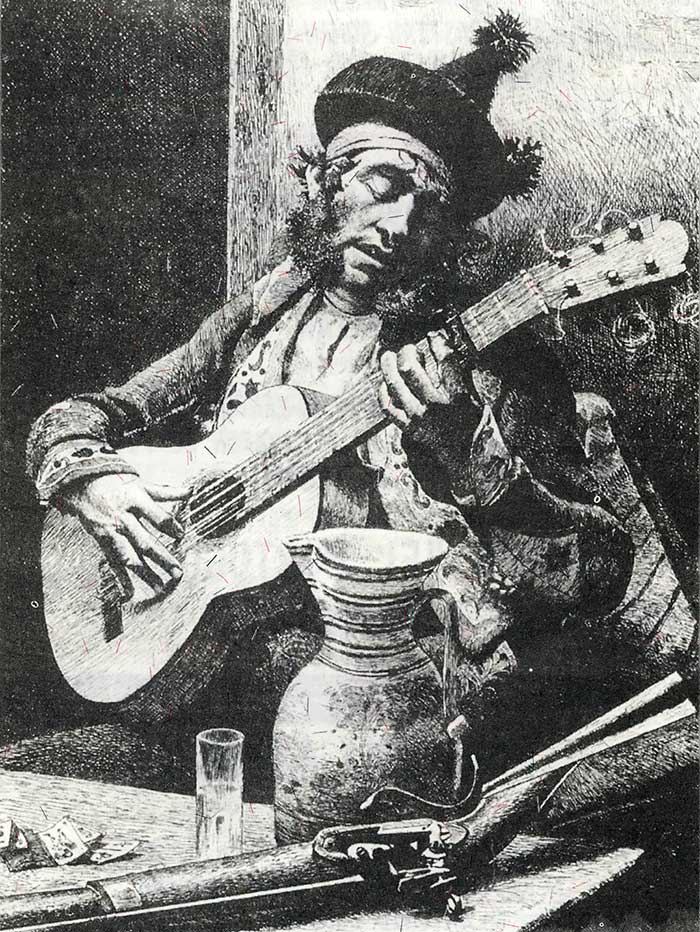

While we were supping with our Drawcansir friend, we heard the notes of a guitar, and the click of castanets, and presently a chorus of voices singing a popular air. In fact mine host had gathered together the amateur singers and musicians, and the rustic belles of the neighborhood, and, on going forth, the courtyard or patio of the inn presented a scene of true Spanish festivity. We took our seats with mine host and hostess and the commander of the patrol, under an archway opening into the court; the guitar passed from hand to hand, but a jovial shoemaker was the Orpheus of the place. He was a pleasant-looking fellow, with huge black whiskers; his sleeves were rolled up to his elbows. He touched the guitar with masterly skill, and sang a little amorous ditty with an expressive leer at the women, with whom he was evidently a favorite. He afterwards danced a fandango with a buxom Andalusian damsel, to the great delight of the spectators. But none of the females present could compare with mine host’s pretty daughter, Pepita, who had slipped away and made her toilette for the occasion, and had covered her head with roses; and who distinguished herself in a bolero with a handsome young dragoon. We ordered our host to let wine and refreshment circulate freely among the company, yet, though there was a motley assembly of soldiers, muleteers, and villagers, no one exceeded the bounds of sober enjoyment. The scene was a study for a painter: the picturesque group of dancers, the troopers in their half military dresses, the peasantry wrapped in their brown cloaks; nor must I omit to mention the old meagre Alguazil, in a short black cloak, who took no notice of any thing going on, but sat in a corner diligently writing by the dim light of a huge copper lamp, that might have figured in the days of Don Quixote.

The following morning was bright and balmy, as a May morning ought to be, according to the poets. Leaving Arahal at seven o’clock, with all the posada at the door to cheer us off we pursued our way through a fertile country, covered with grain and beautifully verdant; but which in summer, when the harvest is over and the fields parched and brown, must be monotonous and lonely; for, as in our ride of yesterday, there were neither houses nor people to be seen. The latter all congregate in villages and strongholds among the hills, as if these fertile plains were still subject to the ravages of the Moor.

At noon we came to where there was a group of trees, beside a brook in a rich meadow. Here we alighted to make our midday meal. It was really a luxurious spot, among wild flowers and aromatic herbs, with birds singing around us. […]

Towards five o’clock we arrived at Osuna, a town of fifteen thousand inhabitants, situated on the side of a hill, with a church and a ruined castle. The posada was outside of the walls; it had a cheerless look. The evening being cold, the inhabitants were crowded round a brasero in a chimney corner; and the hostess was a dry old woman, who looked like a mummy. Every one eyed us askance as we entered, as Spaniards are apt to regard strangers; a cheery, respectful salutation on our part, caballeroing them and touching our sombreros, set Spanish pride at ease; and when we took our seat among them, lit our cigars, and passed the cigar-box round among them, our victory was complete. I have never known a Spaniard, whatever his rank or condition, who would suffer himself to be outdone in courtesy; and to the common Spaniard the present of a cigar (puro) is irresistible. Care, however, must be taken never to offer him a present with an air of superiority and condescension; he is too much of a caballero to receive favors at the cost of his dignity.

Leaving Osuna at an early hour the next morning, we entered the sierra or range of mountains. The road wound through picturesque scenery, but lonely; and a cross here and there by the road side, the sign of a murder, showed that we were now coming among the “robber haunts.” This wild and intricate country, with its silent plains and valleys intersected by mountains, has ever been famous for banditti. It was here that Omar Ibn Hassan, a robber-chief among the Moslems, held ruthless sway in the ninth century, disputing dominion even with the caliphs of Cordova. This too was a part of the regions so often ravaged during the reign of Ferdinand and Isabella by Ali Atar, the old Moorish alcayde of Loxa, father-in-law of Boabdil, so that it was called Ali Atar’s garden, and here “Jose Maria,” famous in Spanish brigand story, had his favorite lurking places.

In the course of the day we passed through Fuente la Piedra near a little salt lake of the same name, a beautiful sheet of water, reflecting like a mirror the distant mountains. We now came in sight of Antiquera, that old city of warlike reputation, lying in the lap of the great sierra which runs through Andalusia. A noble vega spread out before it, a picture of mild fertility set in a frame of rocky mountains. Crossing a gentle river we approached the city between hedges and gardens, in which nightingales were pouring forth their evening song. About nightfall we arrived at the gates.

Pursuing our course through a spacious street, we put up at the posada of San Fernando. As Antiquera, though a considerable city, is, as I observed, somewhat out of the track of travel, I had anticipated bad quarters and poor fare at the inn. I was agreeably disappointed, therefore, by a supper table amply supplied, and what were still more acceptable, good clean rooms and comfortable beds. Our man, Sancho, felt himself as well off as his namesake, when he had the run of the duke’s kitchen, and let me know, as I retired for the night, that it had been a proud time for the alforjas.

Early in the morning (May 4th) I strolled to the ruins of the old Moorish castle, which itself had been reared on the ruins of a Roman fortress. Here, taking my seat on the remains of a crumbling tower, I enjoyed a grand and varied landscape, beautiful in itself, and full of storied and romantic associations; for I was now in the very heart of the country famous for the chivalrous contests between Moor and Christian. […] Beyond spread out the vega, covered with gardens and orchards and fields of grain and enamelled meadows, inferior only to the famous vega of Granada. To the right the Rock of the Lovers stretched like a cragged promontory into the plain, whence the daughter of the Moorish alcayde and her lover, when closely pursued, threw themselves in despair.

The matin peal from church and convent below me rang sweetly in the morning air, as I descended. The market-place was beginning to throng with the populace, who traffic in the abundant produce of the vega; for this is the mart of an agricultural region. In the market-place were abundance of freshly plucked roses for sale; for not a dame or damsel of Andalusia thinks her gala dress complete without a rose shining like a gem among her raven tresses.

Leaving Antiquera at eight O’clock, we had a delightful ride along the little river, and by gardens and orchards, fragrant with the odors of spring and vocal with the nightingale. […]

At noon we halted in sight of Archidona, in a pleasant little meadow among hills covered with olive-trees. […]

Our afternoon’s ride took us through a steep and rugged defile of the mountains, called Puerto del Rey, the Pass of the King; being one of the great passes into the territories of Granada, and the one by which King Ferdinand conducted his army. Towards sunset the road, winding round a hill, brought us in sight of the famous little frontier city of Loxa, which repulsed Ferdinand from its walls. Its Arabic name implies “guardian,” and such it was to the vega of Granada, being one of its advanced guards. It was the strong-hold of that fiery veteran, old Ali Atar, father-in-law of Boabdil; and here it was that the latter collected his troops, and sallied forth on that disastrous foray which ended in the death of the old alcayde and his own captivity. From its commanding position at the gate, as it were, of this mountain pass, Loxa has not unaptly been termed the key of Granada. It is wildly picturesque; built along the face of an arid mountain. The ruins of a Moorish alcazar or citadel crown a rocky mound which rises out of the centre of the town. The river Xenil washes its base, winding among rocks, and groves, and gardens, and meadows, and crossed by a Moorish bridge. Above the city all is savage and sterile, below is the richest vegetation and the freshest verdure. A similar contrast is presented by the river; above the bridge it is placid and grassy, reflecting groves and gardens; below it is rapid, noisy and tumultuous. The Sierra Nevada, the royal mountains of Granada, crowned with perpetual snow, form the distant boundary to this varied landscape; one of the most characteristic of romantic Spain.

Alighting at the entrance of the city, we gave our horses to Sancho to lead them to the inn, while we strolled about to enjoy the singular beauty of the environs. As we crossed the bridge to a fine alameda, or public walk, the bells tolled the hour of oration. […]

We were roused from this quiet state of enjoyment by the voice of our trusty squire hailing us from a distance. He came up to us, out of breath. “Ah, senores,” cried he, “el pobre Sancho no es nada sin Don Quixote.” (”Ah, senores, poor Sancho is nothing without Don Quixote.”) He had been alarmed at our not coming to the inn; Loxa was such a wild mountain place, full of contrabandistas, enchanters, and infiernos; he did not well know what might have happened, and set out to seek us, inquiring after us of every person he met, until he traced us across the bridge, and, to his great joy, caught sight of us strolling in the alameda.

The inn to which he conducted us was called the Corona, or Crown, and we found it quite in keeping with the character of the place, the inhabitants of which seem still to retain the bold, fiery spirit of the olden time. The hostess was a young and handsome Andalusian widow, whose trim basquina of black silk, fringed with bugles, set off the play of a graceful form and round pliant limbs. Her step was firm and elastic; her dark eye was full of fire, and the coquetry of her air, and varied ornaments of her person, showed that she was accustomed to be admired.

She was well matched by a brother, nearly about her own age; they were perfect models of the Andalusian majo and maja. He was tall, vigorous, and well-formed, with a clear olive complexion, a dark beaming eye, and curling chestnut whiskers that met under his chin. He was gallantly dressed in a short green velvet jacket, fitted to his shape, profusely decorated with silver buttons, with a white handkerchief in each pocket. He had breeches of the same, with rows of buttons from the hips to the knees; a pink silk handkerchief round his neck, gathered through a ring, on the bosom of a neatly-plaited shirt; a sash round the waist to match; bottinas, or spatterdashes, of the finest russet leather, elegantly worked, and open at the calf to show his stockings and russet shoes, setting off a well-shaped foot.

As he was standing at the door, a horseman rode up and entered into low and earnest conversation with him. He was dressed in a similar style, and almost with equal finery — a man about thirty, square-built, with strong Roman features, handsome, though slightly pitted with the small-pox; with a free, bold, and somewhat daring air. His powerful black horse was decorated with tassels and fanciful trappings, and a couple of broad-mouthed blunderbusses hung behind the saddle. He had the air of one of those contrabandistas I have seen in the mountains of Ronda, and evidently had a good understanding with the brother of mine hostess; nay, if I mistake not, he was a favored admirer of the widow. In fact, the whole inn and its inmates had something of a contrabandista aspect, and a blunderbuss stood in a corner beside the guitar. The horseman I have mentioned passed his evening in the posada, and sang several bold mountain romances with great spirit. As we were at supper, two poor Asturians put in in distress, begging food and a night’s lodging. They had been waylaid by robbers as they came from a fair among the mountains, robbed of a horse, which carried all their stock in trade, stripped of their money, and most of their apparel, beaten for having offered resistance, and left almost naked in the road. My companion, with a prompt generosity natural to him, ordered them a supper and a bed, and gave them a sum of money to help them forward towards their home.

As the evening advanced, the dramatis personae thickened. A large man, about sixty years of age, of powerful frame, came strolling in, to gossip with mine hostess. He was dressed in the ordinary Andalusian costume, but had a huge sabre tucked under his arm, wore large moustaches, and had something of a lofty swaggering air. Every one seemed to regard him with great deference.

Our man Sancho whispered to us that he was Don Ventura Rodriguez, the hero and champion of Loxa, famous for his prowess and the strength of his arm. In the time of the French invasion he surprised six troopers who were asleep: he first secured their horses, then attacked them with his sabre, killed some, and took the rest prisoners. For this exploit the king allows him a peseta (the fifth of a duro, or dollar) per day, and has dignified him with the title of Don.

I was amused to behold his swelling language and demeanor. He was evidently a thorough Andalusian, boastful as brave. His sabre was always in his hand or under his arm. He carries it always about with him as a child does her doll, calls it his Santa Teresa, and says, “When I draw it, the earth trembles” (”tiembla la tierra”).

I sat until a late hour listening to the varied themes of this motley group, who mingled together with the unreserve of a Spanish posada. We had contrabandista songs, stories of robbers, guerilla exploits, and Moorish legends. The last were from our handsome landlady, who gave a poetical account of the infiernos, or infernal regions of Loxa, dark caverns, in which subterranean streams and waterfalls make a mysterious sound. The common people say that there are money-coiners shut up there from the time of the Moors, and that the Moorish kings kept their treasures in those caverns. […]

Throughout all Spain the men, however poor, have a gentleman-like abundance of leisure, seeming to consider it the attribute of a true cavaliero never to be in a hurry; but the Andalusians are gay as well as leisurely, and have none of the squalid accompaniments of idleness. The adventurous contraband trade which prevails throughout these mountain regions, and along the maritime borders of Andalusia, is doubtless at the bottom of this galliard character.

In contrast to the costume of these groups was that of two long-legged Valencians conducting a donkey, laden with articles of merchandise, their musket slung crosswise over his back ready for action. They wore round jackets (jalecos), wide linen bragas or drawers scarce reaching to the knees and looking like kilts, red fajas or sashes swathed tightly round their waists, sandals of espartal or bass weed, colored kerchiefs round their heads somewhat in the style of turbans but leaving the top of the head uncovered; in short, their whole appearance having much of the traditional Moorish stamp.

On leaving Loxa we were joined by a cavalier, well mounted and well armed, and followed on foot by an escopetero or musketeer. He saluted us courteously, and soon let us into his quality. He was chief of the customs, or rather, I should suppose, chief of an armed company whose business it is to patrol the roads and look out for contrabandistas. The escopetero was one of his guards. In the course of our morning’s ride I drew from him some particulars concerning the smugglers, who have risen to be a kind of mongrel chivalry in Spain. They come into Andalusia, he said, from various parts, but especially from La Mancha, sometimes to receive goods, to be smuggled on an appointed night across the line at the plaza or strand of Gibraltar, sometimes to meet a vessel, which is to hover on a given night off a certain part of the coast. They keep together and travel in the night. In the daytime they lie quiet in barrancos, gullies of the mountains or lonely farm-houses; where they are generally well received, as they make the family liberal presents of their smuggled wares. Indeed, much of the finery and trinkets worn by the wives and daughters of the mountain hamlets and farm-houses are presents from the gay and open-handed contrabandistas.

Arrived at the part of the coast where a vessel is to meet them, they look out at night from some rocky point or headland. If they descry a sail near the shore they make a concerted signal; sometimes it consists in suddenly displaying a lantern three times from beneath the folds of a cloak. If the signal is answered, they descend to the shore and prepare for quick work. The vessel runs close in; all her boats are busy landing the smuggled goods, made up into snug packages for transportation on horseback. These are hastily thrown on the beach, as hastily gathered up and packed on the horses, and then the contrabandistas clatter off to the mountains. They travel by the roughest, wildest, and most solitary roads, where it is almost fruitless to pursue them. […]

Towards noon our wayfaring companion took leave of us and turned up a steep defile, followed by his escopetero; and shortly afterwards we emerged from the mountains, and entered upon the far famed Vega of Granada.

Our last mid-day’s repast was taken under a grove of olive-trees on the border of a rivulet. We were in a classical neighborhood; for not far off were the groves and orchards of the Soto de Roma. This, according to fabulous tradition, was a retreat founded by Count Julian to console his daughter Florinda. It was a rural resort of the Moorish kings of Granada, and has in modern times been granted to the Duke of Wellington.

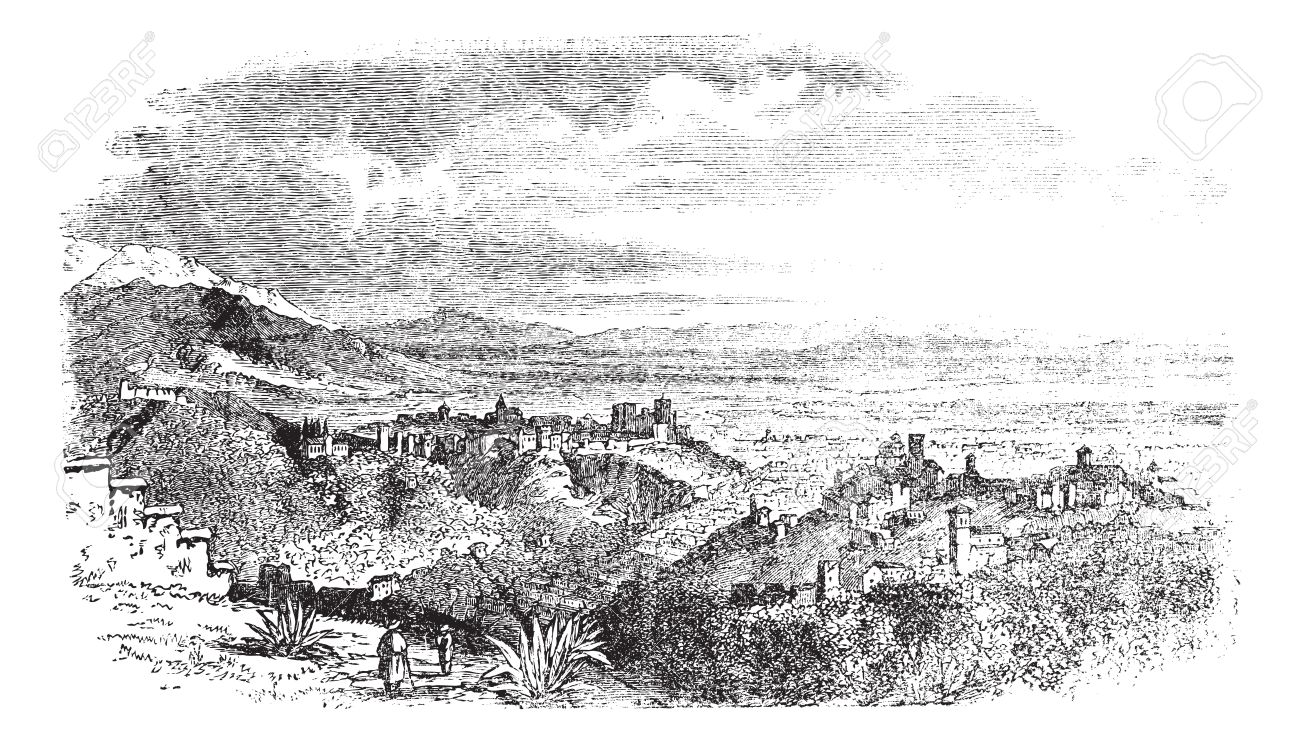

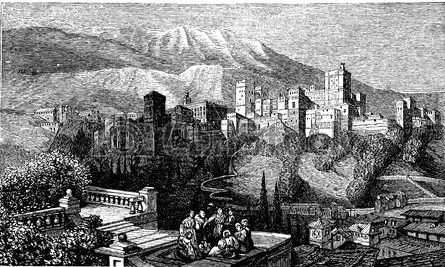

[…] The day was without a cloud. The heat of the sun was tempered by cool breezes from the mountains. Before us extended the glorious Vega. In the distance was romantic Granada surmounted by the ruddy towers of the Alhambra, while far above it the snowy summits of the Sierra Nevada shone like silver.

Our repast finished, we spread our cloaks and took our last siesta al fresco, lulled by the humming of bees among the flowers and the notes of doves among the olive-trees. When the sultry hours were passed we resumed our journey. After a time we overtook a pursy little man, shaped not unlike a toad and mounted on a mule. He fell into conversation with Sancho, and finding we were strangers, undertook to guide us to a good posada. He was an escribano (notary), he said, and knew the city as thoroughly as his own pocket. “Ah Dios, senores! what a city you are going to see. Such streets! such squares! such palaces! and then the women — ah Santa Maria purisima — what women!” “But the posada you talk of,” said I; “are you sure it is a good one?”

“Good! Santa Maria! the best in Granada. Salones grandes — camas de luxo — colchones de pluma (grand saloons — luxurious sleeping rooms — beds of down). Ah, senores, you will fare like King Chico in the Alhambra.”

“And how will my horses fare?” cried Sancho.

“Like King Chico’s horses. Chocolate con leche y bollos para almuerza” (”chocolate and milk with sugar cakes for breakfast”), giving the squire a knowing wink and a leer. […]

Thus escorted, we passed between hedges of aloes and Indian figs, and through that wilderness of gardens with which the Vega is embroidered, and arrived about sunset at the gates of the city. Our officious little conductor conveyed us up one street and down another, until he rode into the courtyard of an inn where he appeared to be perfectly at home. Summoning the landlord by his Christian name, he committed us to his care as two caballeros de mucho valor, worthy of his best apartments and most sumptuous fare. We were instantly reminded of the patronizing stranger who introduced Gil Blas with such a flourish of trumpets to the host and hostess of the inn at Pennaflor, ordering trouts for his supper, and eating voraciously at his expense. “You know not what you possess,” cried he to the innkeeper and his wife. “You have a treasure in your house. Behold in this young gentleman the eighth wonder of the world — nothing in this house is too good for Senor Gil Blas of Santillane, who deserves to be entertained like a prince.”

Determined that the little notary should not eat trouts at our expense, like his prototype of Pennaflor, we forbore to ask him to supper; nor had we reason to reproach ourselves with ingratitude; for we found before morning the little varlet, who was no doubt a good friend of the landlord, had decoyed us into one of the shabbiest posadas in Granada.