On February 6, 1939, to save his life, my grandfather crossed the border leaving behind his country ravaged by civil war. He would never set foot on Spanish soil again except on a few occasions when his friends would take him to the mountains where he could technically for a few moments kiss the ground of his beloved motherland.

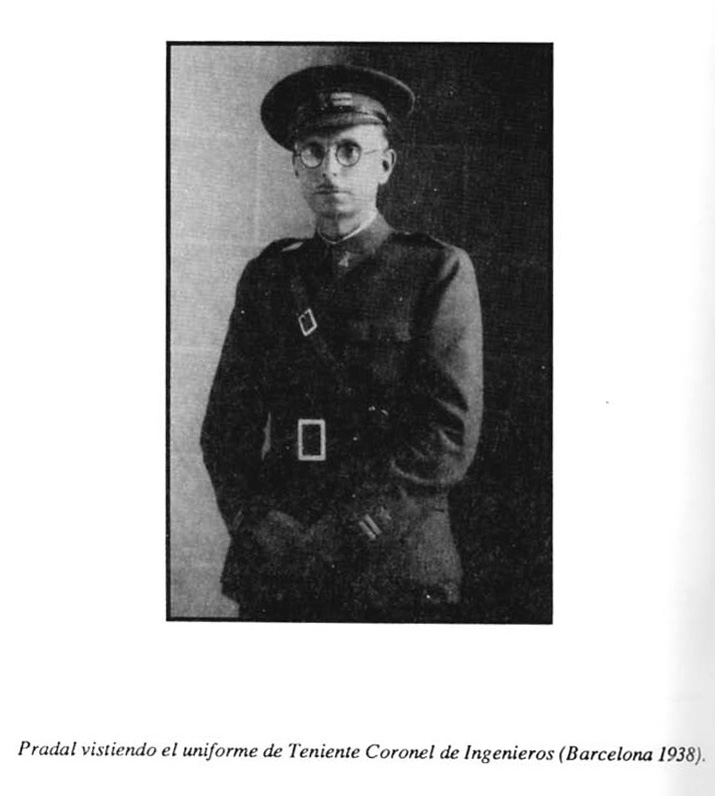

He was the last congressman of the Spanish Republic to leave their country. Son of a well to do Andalusian family he was a co-founder of the Spanish Socialist Party. Because he was an architect he had been in charge of Barcelona’s fortifications. Now the city had fallen and in the middle of one of the worse winter on record he was walking into a foreign country. He and tens of thousands like him did not find a friendly welcome. He was guided to the infamous camp of Argelès. Fortunately, he spent only two days on that squalid beach, thanks to the owner of the Terminus Hotel in Perpignan.

Others were not that lucky.

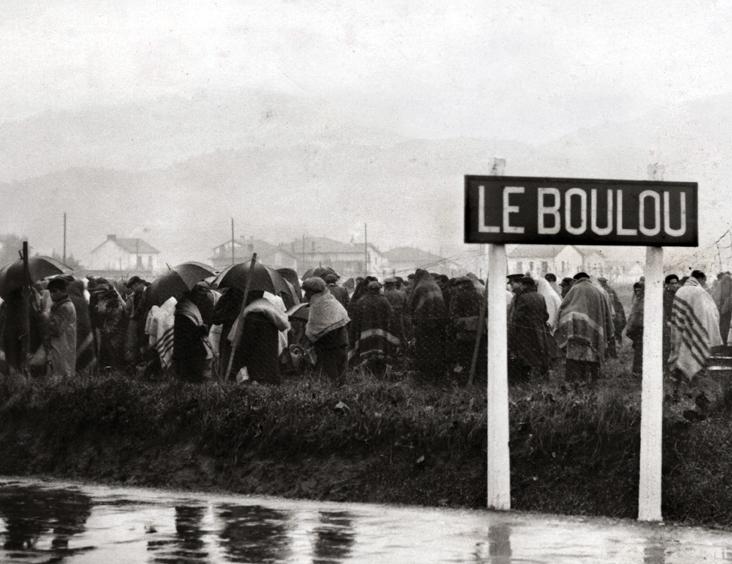

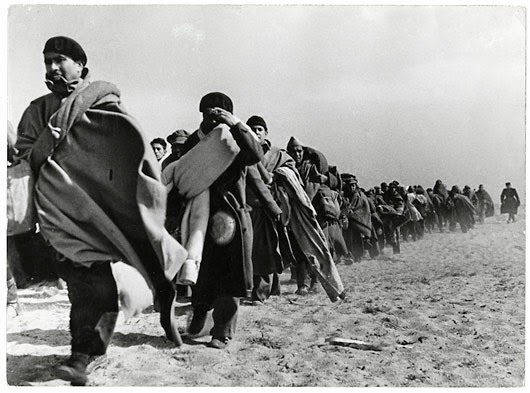

January 26, 1939, Barcelona falls in the hands of the franquistes. After three years of a civil war that has covered the whole Spain with blood, the defeated ones are the republicans. Pushed by machine-guns they, civild and soldiers escape to the border to take refuge in France. On January 27 the border is open, the first civil refugees enter France, while the last combatants continue the struggle until the beginning of February.

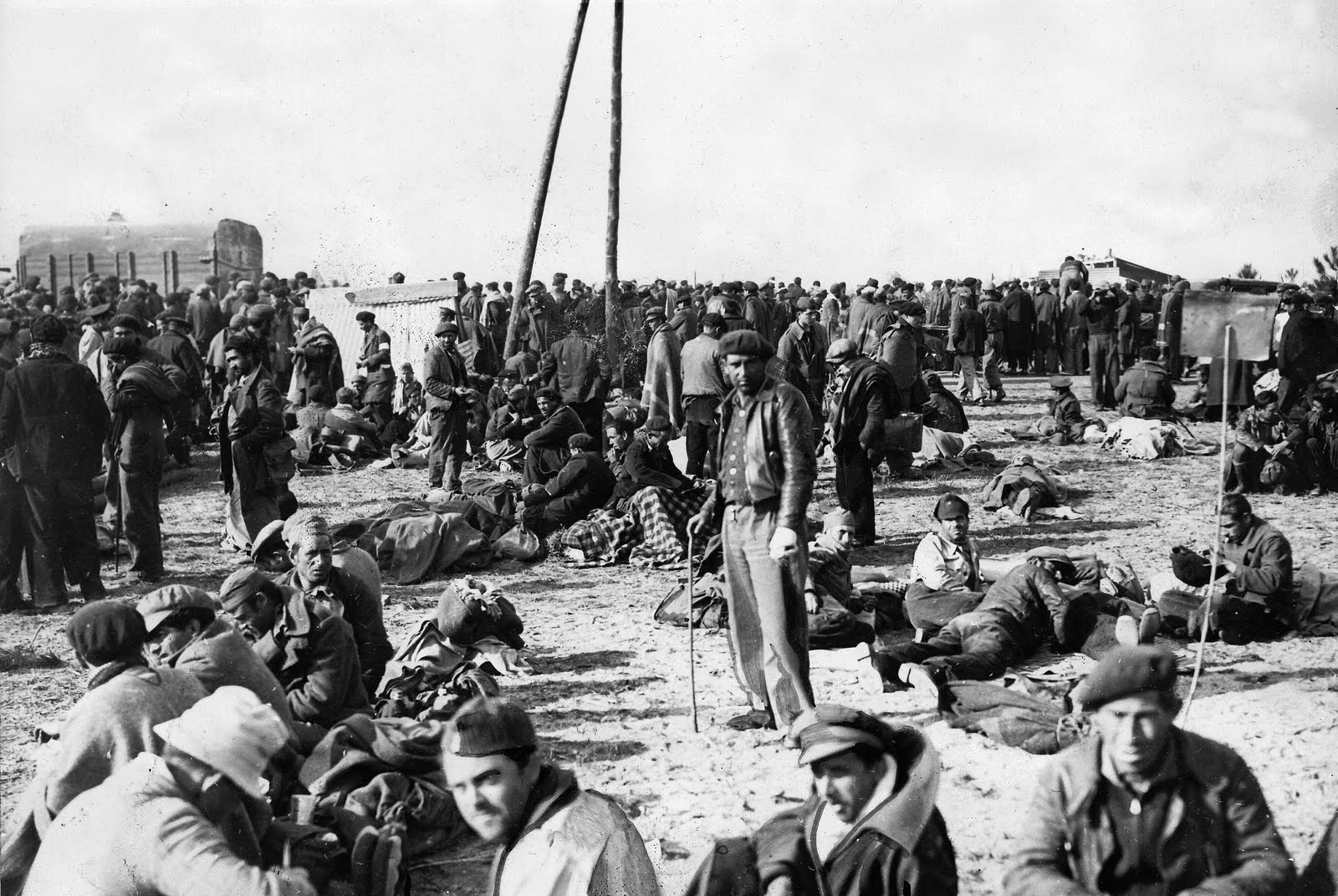

This exode is called the “Retirada”. Facing the arrival of almost a half-million people, the French authorities choose to concentrate the refugees close to the border to prevent that they disperse and thus to be able to control them.

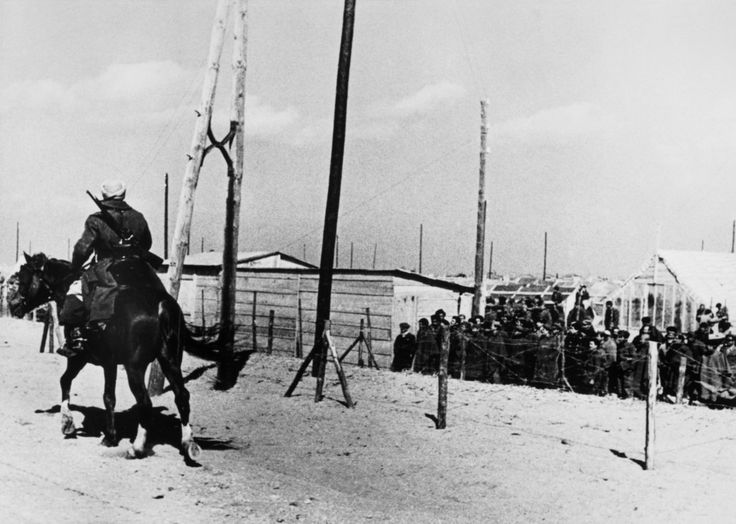

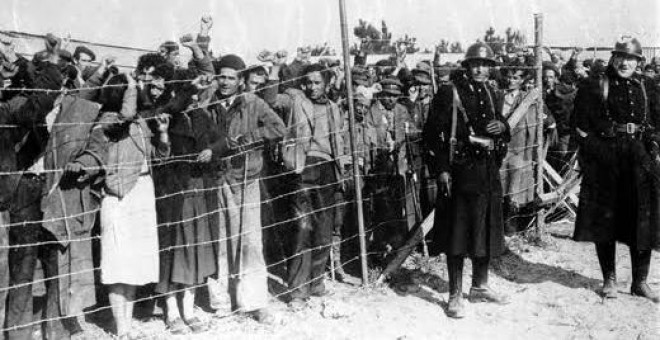

At first the border remained closed to the republican army pursued by the franquistes. Then under international public opinion pressure, the president Daladier decides to let what remains of the republican army to enter. Families are separated. The men are sent to the Argelès and Saint Cyprien camps on the beaches. They are concentration camps built by the republicans themselves. These camps are barbed, the surveillance is ensured by Senegalese riflemen and mobile guards.

The weather conditions were terrible. It was a snowy winter. Civilian men, women and children passed the border on foot through the mountain together with the soldiers. Dispersed relatives were looking for eachother.

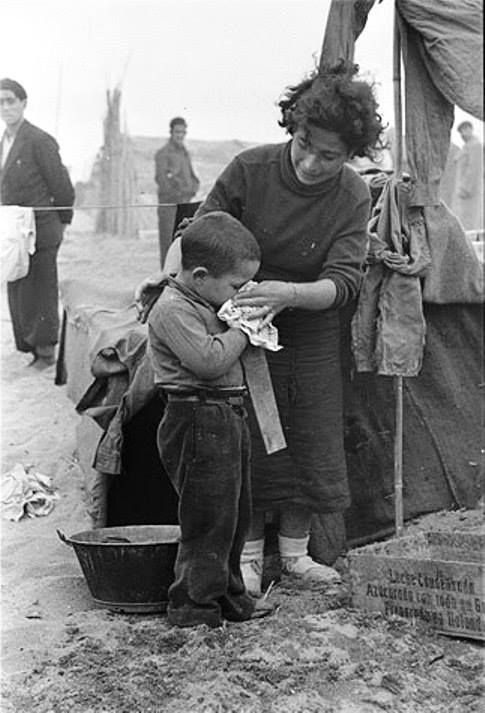

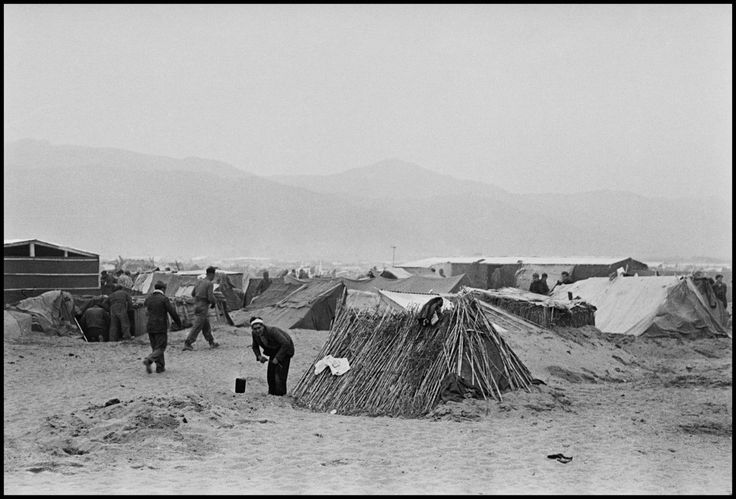

Around mid-March 1939, the war photographer Robert Capa visited the enormous concentration camp of Argelès-plage where were interned nearly 75.000 Spanish republicans. Capa described this camp as “a hell on sand”: “the men there survive under tents of fortune and huts of straw offering only poor protection against wretched cold sand and wind. In addition, there is no drinking water, only the brackish water extracted from holes dug in the sand.”

The establishment of two other camps in the vicinity followed: Saint-Cyprien and Barcarès. No shelters, no latrines, no kitchen, no infirmary not even electricity. Everywhere dysentery prevailed. Very quickly, the patients and the casualties burdened the hospitals of the region. In Argelès and Saint-Cyprien, the camps held a hundred and eighty thousand men and women. In Barcarès, seventy thousand were incarcerated.

These camps multiplied as those of Bram and Gurs were added. As a plate affixed to the entry of the later camp attests, there «stayed» 23 000 Spanish combatants, 7 000 international Brigades volunteers, 120 French patriots and resistants, 12 860 immigrant Jews interned in May-June 1940, 6500 German Jews of the country of Bade, 12 000 Jews arrested by the Vichy police.

Indeed, these camps, in particular Rivesaltes and Gurs, at first built for the Spanish republicans would become useful to the Vichy government, to imprison resistants, Jews and gipsies… Each day, the gendarmes would invite the Spanish prisoners to return to Spain or to engage in the foreign Legion. Famished, the luckiest ones served as hand-workers for the farmers of the area.

Later the obligatory work started, and after June 1940, Vichy gives the prisoners to the Germans in need of labor. One part of the prisoners was deported to Germany, to camps of another nature: Dachau, Buchenwald and Mathausen, where six thousand seven hundred Spaniards perished. When the war was declared, many Spaniards, who still had the bitter taste of the defeat in their mouth, enroll in the Marching Battalions of the Foreign Volunteers or the Foreign Legion.