COSTA DEL SOL (continued)

by Clotilde Bernadi-Pradal

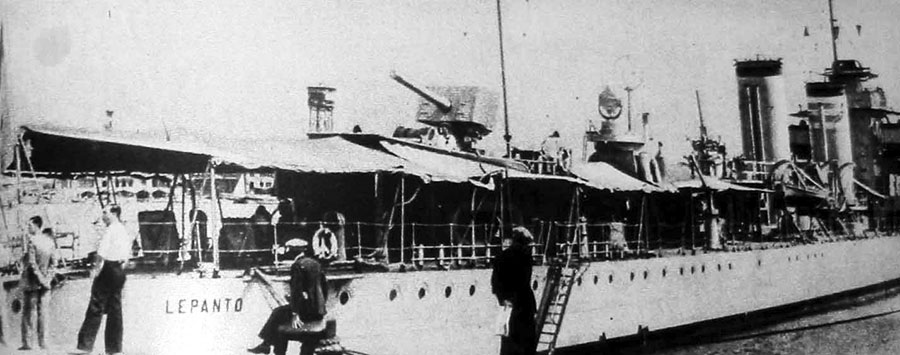

On July 18th, the military uprising shook all of Spain. At the prefecture of Almería, a few men stood up against the regional General and the Civil Guard commander. The situation was desperate for the Republicans when they saw, with a mix of hope and fear, the battleship “Lepanto” enter the port of Almería. It was lead by a lieutenant commander who, having pointed its guns towards the barracks, vigorously summoned the insurgents to raise their white flag. After a few minutes, which felt like centuries, the flag rose slowly on a sky so blue: Almería would remain Republican for another three years. Malaga for a few months. It would not be the case for Granada where the defeat of the government led to a horrible massacre from which Federico Garcia Lorca would not escape.

Therefore, the front was established between the province of Granada and those of Malaga and Almería. Our Aguadulce road, once so quiet, was now to become a small part of the stage where the Spanish tragedy would unfold.

The People’s Army was organized with makeshift means: mining dynamite, shotguns, etc. Truckloads of men dressed in “mono Azul” blue overalls, were passing through the village towards the front. Standing, pressed against each other, the men sang merrily:

“If you want to write to me

You know my whereabouts

At the Motril front

First firing line.”

At first they stopped to drink at the inn, then I do not know exactly why they got into the habit of stopping at our home where a huge white clay jug “botijo”, full of fresh water, remained at all times on the low wall that separated the house from the road. Kalin had carefully written on the “botijo” three large blue letters: U.H.P. – Union Hermanos Prolétarios. This big “botijo”, from then on called the “U.H.P. “, became famous among the men heading to the front or returning from it. We must not forget that in Spain, especially in the South, men drink water with interest, tasting it, comparing it with other sources as real connoisseurs.

The disturbances and anxiety of that time did not spare the children; I began to have sleepless nights mulling the atrocious stories I heard during the day. We did not have the heart to go down to the beach or to lose ourselves in our romantic explorations.

One morning, when the air was extraordinarily transparent, the sea absolutely calm, before the sun began to burn, and when a near frightening quietude reigned, we saw by the coast in the direction of Almería a mysterious black ship with no flag. (Aguadulce is eight kilometers from Almería and we could clearly see what was going on.) It stopped in front of the port and immediately we heard terrible explosions: it had just bombarded the oil deposits, which spread in flames over the sea becoming a strange and enormous fire that could not be extinguished until evening. The boat turned back slowly on itself and we saw it quietly pass once more in front of us at a slow cruising pace. On the beach, for a long time following, we found burned discolored fish, these fish whose vivid shades we knew so well.

There was no question of returning to Madrid to start school. The holidays were prolonged for us and the climate, was literally still like summer when Christmas arrived. This was our first Three Kings celebration without gifts. I remember having cried, but Mommy, no doubt, was the most mortified.

Wounded men came to live in a small house in the village. Sometimes they came out by the road and spoke strange languages, perhaps French, Romanian, Lethon? – The International Brigades had gathered more than forty nationalities. They would later leave, having had no contact established with the population. In addition to the German explorer, it was the second time we heard foreigners in Aguadulce.

Our lives had become confused; I do not know exactly what we were making of our days. Still, I would go to school in the village, where we learned that lungs were two fleshy reddish, spongy masses, or how the silkworms breed. We also did collages with glossy papers.

In early February the traffic towards the front intensified. Malaga was suffering the Italian offensive, experienced and so well told by Arthur Koestler in his “Spanish Testament”. The exodus towards Almería began. Continuously, women, old men, children were passing in rags on foot, bent and starving. At night, groups would stop in a kind of warehouse next to our house. I remember accompanying my aunts there throughout the night, by candlelight – we no longer had electricity – distributing cups of steaming coffee, passing over exhausted bodies, motionless, piled up on the cement floor. These Dantesque scenes never stopped torturing me.

That is when our departure from Aguadulce was suddenly decided upon. One night they made us get up and get in cars. There was only room for people. Daddy was adamant: we were forbidden to take anything whatsoever. “Tereso” the beautiful white pigeon who lived freely in the house, had to stay there, as well as “Vallejo” the extraordinarily giant rabbit who we enjoyed and who shared our privacy.

I did not resign myself to abandoning “Pecoso”, the red and white cat who one must believe had secret charm only for me because everyone else found him horrible and rude. “Pecoso” meant a lot in my life. I hid him under my clothes. I was pushed into the back of a black car which was already overloaded. Do not meow, “Pecoso”! No! He too, left Aguadulce silent and sad.

Costa del Sol! I recently received a postcard from Aguadulce, showing a magnificent four-star hotel. It is not the only one in the area, there is another more beautiful one with bamboo, very close to “our” beach where they say Brigitte Bardot likes to stay. Tourists believe that they have finally discovered these unknown beaches where restaurants and merchants of great variety abound. There are many tall modern residences instead of square, white, small houses; the inn still exists, but is adapted to modern tastes. Only Don Emilio’s grocery is still standing, the last witness of a time when consumption was only a necessity, not a hobby or the purpose of existence.

On the site of our home with jasmine and heliotrope now creeps a large camp ground, “great accommodations” indicated on all road maps. The flat scrubland stretching from the road to the cemetery has become, with German cultivation techniques, a real vegetable field covered with tomatoes and peppers. As everyone knows the hinterland, still wild, served as a film location, and Sergio Leone in particular, was able to draw great effects from it. The cave of the gypsies is now deserted. For them, some humble “low-income housing” was built to spare the tourists the embarrassing spectacle of cave dwellings.

How can one not rejoice in this progress despite the nostalgia for what these places once represented to our privileged childhood? But the other children, those who were fed the “caldo con nene”, what have they become in the midst of these new multilingual residents? Certainly today, there is vermicelli in their children’s soup, but how does the progress in their lives relate to the enormous progress made in their country?

How can one not rejoice in this progress despite the nostalgia for what these places once represented to our privileged childhood? But the other children, those who were fed the “caldo con nene”, what have they become in the midst of these new multilingual residents? Certainly today, there is vermicelli in their children’s soup, but how does the progress in their lives relate to the enormous progress made in their country?

All I know is that they will no longer fetch water at the little spring because they have running water in their sinks, but they say this fresh water, once so sweet, now has a bitter aftertaste.

One response to “SPANISH SUNSET”

What a treasure to have this memoir from your mother. It’s a breathtaking document of history unknown to most of us. Lovely – thank you for sharing!