Some eighty years ago, several thousand young Americans went to Spain to fight — and, many of them, to die — in the service of a country that was not their own.

Nothing like that had happened on such a scale before, and nothing like it has happened since. They went despite the active opposition of their own government, which would treat them, upon their return and for many years thereafter, as politically suspect. They left jobs, schools, families, sweethearts. They went to enlist on the side of the Republic in the Spanish Civil War, the great cause of the day, joining more than 40,000 other foreign volunteers from some fifty countries.

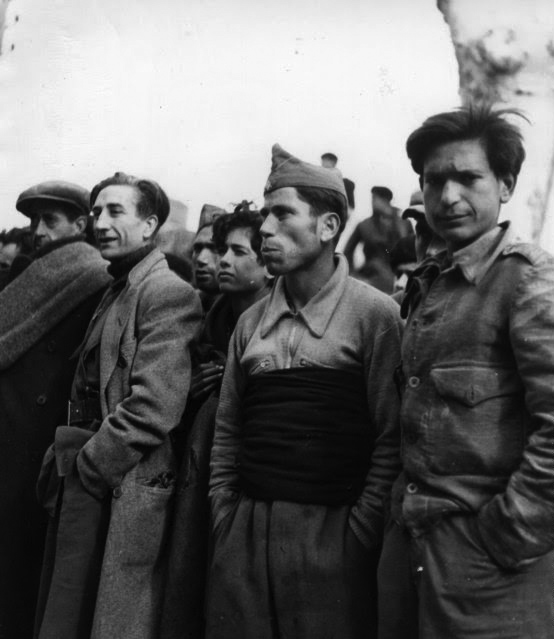

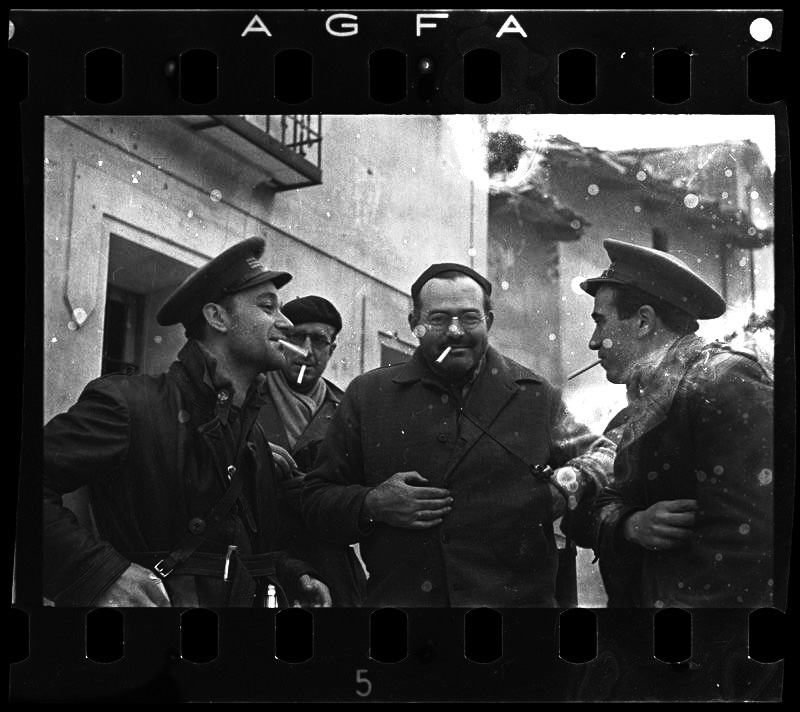

On the morning of February 27, 1937, which began cold and gray, a few hundred Americans waited to storm a hill southeast of Madrid, near the Jarama River. They were volunteer soldiers, drawn to Spain by a noble cause. Germany belonged to Hitler, and Italy to Mussolini, but there was still a chance that the Spanish Republic could fight off a cabal of right-wing generals who called themselves Nationalists. The previous year, the Nationalists had tried to take over the country, touching off a civil was. Leftist volunteers from around the world flocked to the Republican side, seeing the was as a struggle between tyranny and freedom that transcended national boundaries. The fight felt almost holy – “like the feeling you expected to have and did not have when you made your first communion,” Ernest Hemingway wrote, in “For Whom the Bell Tolls.”

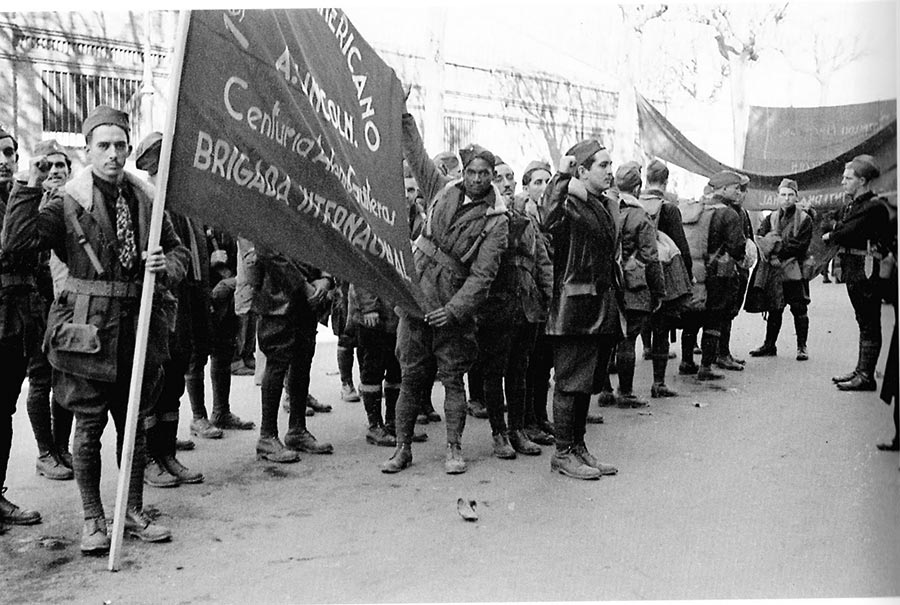

The Americans had been brought to Spain by Comintern, the worldwide Communist organization, but, to disguise their allegiance, the troops had been given an irreproachably non-Communist name: the Abraham Lincoln battalion.

Entrenched at the top of the hill behind a shot-up olive grove, were Moorish troops, flown in from Spain’s protectorate in Morocco in planes furnished by Hitler and Mussolini. The Moors were known to be especially formidable. “They were terrifying. Masters of an art that comes to a man after a lifetime spent with a rifle in his had.”

Whereas Spain’s right united within a few months around a single leader – the cunning, ruthless Francisco France, who went on to rule as a dictator for three and a half decades – the left tore itself apart with squabbling and paranoia. Veterans came to feel that the idealism of the cause had been exploited, and many resented being policed by shadowy Communist enforcers. Not all were embittered by the experience, however. “We were naïve,” one American recalled, years later, “but it’s the kind of naïveté that the world needs.”

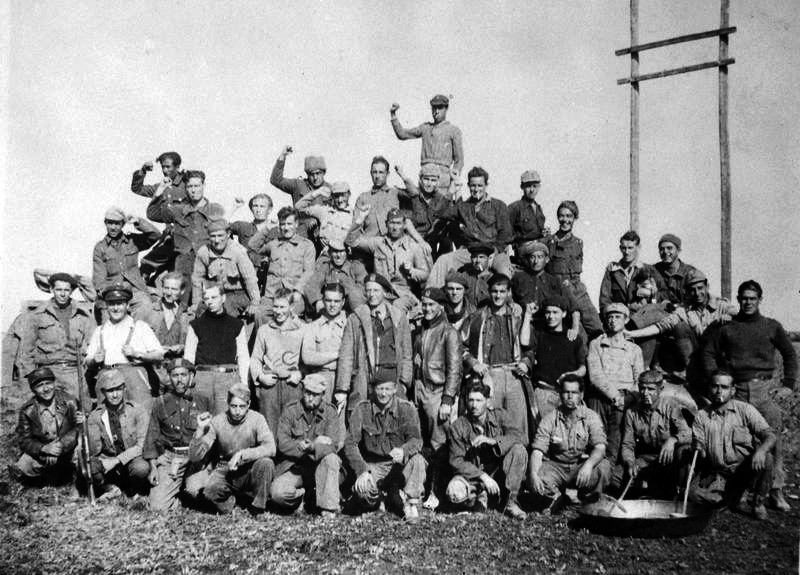

Twenty-eight hundred American volunteers travelled to Spain with the Lincoln battalion. Before enlisting, three-quarters of them had belonged to either America’s Communist Party or the Party’s youth league. A third of the Lincolns came from the New York City area, and an even larger proportion were Jewish. There were more than eighty African-Americans in the battalion, and one became the first of his race to lead white American soldiers into battle. Though a number of women signed up as medical staff, one served in the Lincoln battalion. The typical volunteer was single and in his late twenties. Most were working-class but the range of careers was broad: longshoreman, schoolteacher, miner, vaudeville acrobat, rabbi, journalist. The last surviving Lincoln veteran, Delmer Berg, died in February, at the age of a hundred, before signing up, he was a dishwasher.

In their training base in Albacete, the Lincolns drilled with broomsticks and cane in lieu of rifles, which were scarce, and were harangued by André Marty, the chief organizer of the international forces, about the danger of Trotskyists in their midst. Paranioa among Communists and Stalin loathed him – and few were more paranoid than Marty. He is said to have ordered the execution of hundreds of volunteers. Lincolns were ordered to hand over their passports, purportedly for safekeeping, but a number of them went mysteriously missing at the end of the war – probably passed along to Soviet intelligence. The Stalin agent who assassinated Trotsky, in Mexico in 1940, was travelling on a Canadian passport that had been surrendered this way.

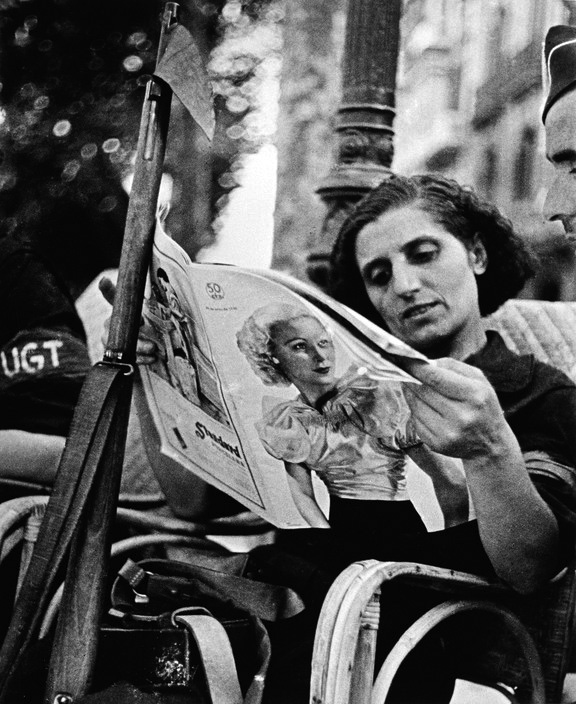

In November, 1936, the Republic’s Prime Minister and cabinet fled, a desertion that, instead of demoralizing the city, unleashed an anarchist, popular enthusiasm for its defense.

The city did not fall until the very end of the war. For two and a half years, it managed to continue life under siege.

John Dos Passos, Antoine de Saint=Exupéry and many other writers stayed at the Hotel Florida, where Hemingway held court, playing Chopin records, loaning his bathtub to soldiers, and sharing ham, cheese, caviar, whiskey, and pâté.

The Lincolns’ final battle was launched in July, when eighty thousand Republican troops crossed the Ebro River in rowboats and on pontoon bridges. The attack surprised the enemy but then crumbled, like many earlier Republican offensives, for lack of equipment.

In September, 1938, the Republic’s Prime Minister announced to the League of Nations that Spain was sending home all its foreign volunteers. It was a peace gesture. Franco, however, refused to negotiate. He wanted to be free to punish the defeated harshly, as he laid the foundation for his dictatorship, which lasted until his death, in 1975, when he was eighty-two. It’s estimated that, in the war’s aftermath, Franco had twenty thousand people killed and sent more than four hundred thousand to prison.

The Republic threw a farewell parade for the Lincolns and other international volunteers in Barcelona, in October, 1938, when the fall of the Republic was still five months off, trying to do justice to the nobility of the volunteers’ sacrifice.

They had fought without the protection and support that their leaders could have provided. More than one out of four died during the Spanish Civil War.

Was the sacrifice betrayed? To win a was requires capital and labor, money to buy guns, tanks, and airplanes, and people to shoot, drive, and fly them. While Spain’s gold should have saved it from asking people to die in great number, its fellow-democracies, fearing Hitler, refused to trade weapons for the gold. As a result, the Spanish Civil War, which claimed around half a million lives, was a battle between capital abetted by Fascism, and labor misled by the poisonous internal politics of the Soviet Union and deserted by its natural allies, the moderate, liberal nations like France, Great Britain, and the United States. The leaders of the Western democracies thought they could postpone a confrontation with Fascism indefinitely. History has proven that although the volunteers from those countries who went to Spain are usually thought of as more idealistic than their leaders, they were in fact more clear-eyed.

“Men of my generation have had Spain in our hearts,” Camus wrote. “It was there that they learned … that one can be right and yet be beaten, that force can vanquish spirit and that there are times when courage is not rewarded.”

References: ![]() This post incorporates text from reviews of the book Spain in Our Hearts: Americans in the Spanish Civil War, 1936–1939, by Adam Hochschild, in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal and The New Yorker.

This post incorporates text from reviews of the book Spain in Our Hearts: Americans in the Spanish Civil War, 1936–1939, by Adam Hochschild, in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal and The New Yorker.